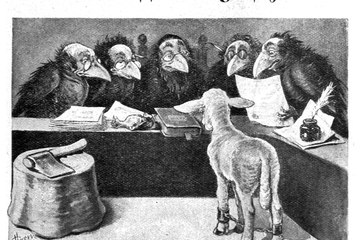

"Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

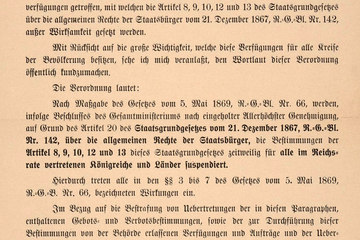

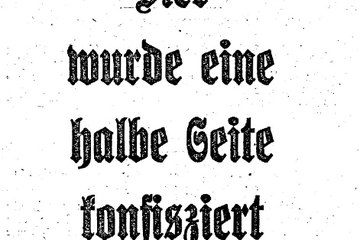

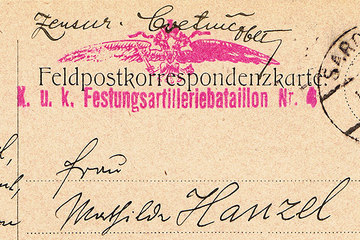

The new military mobilisation led to a system of political coercion in Austria Hungary, which is referred to in the historical literature as "wartime absolutism". This was made possible by several emergency regulations that had already been laid down in the 1867 "December Constitution" in the form of the Emperor's powers to issue emergency decrees, as well as in the right to suspend selected basic rights.