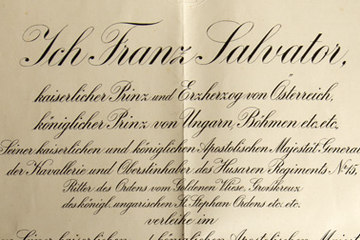

-

War Merit [Kriegshilfsdienst] certificate, 1916

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

War Merit [Kriegshilfsdienst] medal, 1916

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

During the First World War, there was an unprecedented mobilization of the civilian population – and, above all, of women. Their work to support the war effort was not confined to the home; ever more women went to the front as military auxiliaries.

Because of the considerable lack of soldiers who were fit to fight, from 1917, the imperial Ministry of War had to fall back upon female assistance. To relieve some of the pressure on the soldiers who were still fit to fight, what were known as ‘female auxiliaries’ were deployed from March of that year. They were answerable to the Chef des Ersatzwesens für die gesamte bewaffnete Macht [Chief of replacement services for the entire armed services] and were meant to take over certain duties that had previously performed by men so that the latter could join the fighting troops.

The Austro-Hungarian army had already begun to employ women auxiliaries for housekeeping and administrative duties long before 1917. The Rot-Kreuz-Schwestern [Red Cross nurses] had also been serving on the front since 1915. After 1917, however, the military had to significantly increase the number of women in its ranks. Between 1917 and 1918, between 36,000 and 50,000 women were working as auxiliaries on the front.

Female army service was, however, not a peculiarly Austrian phenomenon. The German, British, French and American militaries also deployed female auxiliaries from 1917 onwards. In Germany, they were known as ‘Etappenhelferinnen’. Their activities were often organized by women from the bourgeois women’s movement. They led the women’s departments that were established to mobilize the female workforce throughout Germany.

Like their German counterparts, the auxiliaries of the Austro-Hungarian Empire worked as technical assistants, office staff, telephonists, stenographers, and as cooks, seamstresses and housekeepers. They worked far from home, sometimes side-by-side with the soldiers. Although the military emphasized that the female auxiliaries in the army had no uniform, sketches of their work clothes provide indications to the contrary.

Austro-Hungarian women signed up for military auxiliary service for very different reasons. Alongside patriotism and the opportunity to earn a good wage, the terrible supply shortages at home must have also played a significant role. Women often expected that they would gain better access to supplies if they worked for the army.

The women auxiliaries did not enjoy a good reputation: they were depicted as sexually and morally loose, immoral and adventurous. As the female auxiliaries and ‘Etappenhelferinnen’ – unlike the highly revered Rot-Kreuz-Schwestern [Red Cross nurses] – were not working in caring or nursing roles, they undermined the image of the motherly, loving and caring wartime woman that had previously prevailed. By working in the military, such women threatened the dichotomy of masculine front and feminine home, and with it, the gender system that the logic of war had given rise to.

Translation: Aimee Linekar

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004

Hois, Alexandra: „Weibliche Hilfskräfte“ in der österreichisch-ungarischen Armee im Ersten Weltkrieg (unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit), Wien 2012

Schönberger, Bianca: Mütterliche Heldinnen und abenteuerlustige Mädchen. Rotkreuz-Schwestern und Etappenhelferinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Hagemann, Karen/Schüler-Springorum, Stefanie (Hrsg.): Heimat – Front. Militär und Geschlechterverhältnisse im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Frankfurt/New York 2002, 108-127

Stoehr, Irene/Aurand, Detel: Opfer oder Täter? Frauen im I. Weltkrieg (1), in: Courage (1982), 11, 43-50