For a long time, the imaginary dichotomy between the ‘masculine front’ and ‘feminine homeland’ made it possible to make subtle distinctions between the various fields women worked in during the First World War. Why should we look for them in the trenches when their place was on the home front anyway?

In almost all of the warring countries, a considerable number of women volunteered to serve on the front. They worked not only as nurses or as female auxiliaries in military administration, but were also actively involved in armed battles.

Women’s involvement in fighting was, however, not something that the military had intended or desired. While women auxiliaries were, at least, accepted by society, the deployment of women combatants met with strong opposition both within the army and in society at large. Individual women tried, nonetheless, to advance to the front – often by denying their sex – in order to fight side by side with male soldiers.

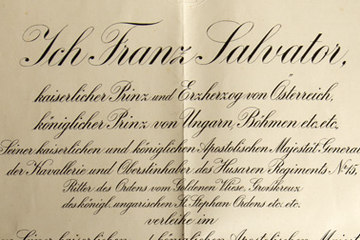

They took part in battle and showed exceptional courage. For this reason, on 3 November 1915, Emperor Franz Joseph decreed that in future, women, too, could receive medals for bravery. For example, Viktoria Savs, known as the ‘heroine of the three peaks’, who followed in her father’s footsteps by joining the second Innsbruck third-class infantry battalion, earned a silver bravery medal for her exceptional service on the front.

Significant numbers of women were also deployed in the Polish and Ukrainian armies. Their participation in fighting units was, however, also unwanted, and so, much like the women auxiliaries, they were confined to nursing, housekeeping and administrative functions. Permission to fight was largely dependent on their advocates and commanders.

For this reason, women often entered the battlefield by masquerading or disguising themselves as male soldiers. In this way, they increased their chances of taking part in battle. Some Polish and Ukrainian women even made it as far as the battlegrounds of the Carpathian Mountains and Volhynia. The precise number of battle-ready female soldiers is, however, impossible to determine due to the lack of historical sources.

The following lyrics of a Ukrainian folk song tell the story of war heroine Olena Stepanivna, who was awarded a silver medal for bravery for her actions during the battle of Makivka in the Carpathian mountains in spring 1915:

Hey, the girls were breaking the rowan twigs, the riflemen were marching down the mountainside. And when they arrived at the bottom, they formed two columns, and chased the Russians away, and were praised. And Olena Stepanivna fought with the riflemen; while they fought for Makivka, she dressed wounds.

The song takes women’s participation in battle as its theme, yet refers to their work treating the wounded. This suggests that it was only in exceptional cases that women were involved in battle, and that they were usually deployed in auxiliary roles. The front is no longer depicted here as a solely masculine arena, and yet the dichotomy of the caring woman and the war-loving man is maintained.

The female soldiers, just like the female auxiliaries, stepped over the imaginary line between the ‘masculine front’ and ‘feminine home’. They knocked wartime gender roles out of kilter, which is why their patriotic commitment – unlike that of the caring and self-sacrificing nurses – was broadly forgotten after the end of the war.

Translation: Aimee Linekar

Daniel, Ute: Frauen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2009, 116-134

Hacker, Hanna: Ein Soldat ist meistens keine Frau. Geschlechterkonstruktionen im militärischen Feld, in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie (1995), 2, 45-63

Heeresgeschichtliches Museum: Die Frau im Krieg. Katalog zur Ausstellung vom 6. Mai bis 26. Oktober 1986, Wien 1986

Leszczawski-Schwerk, Angelique: „Töchter des Volkes“ und „stille Heldinnen“. Polnische und ukrainische Legionärinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Latzel, Klaus/Maubach, Franka/Satjukow, Silke (Hrsg.): Soldatinnen. Gewalt und Geschlecht im Krieg vom Mittelalter bis heute, Paderborn et al. 2001, 179-205

Quotes:

"Hey, the girls were breaking …“: Ukrainisches Volkslied, quoted from: Leszczawski-Schwerk, Angelique: „Töchter des Volkes“ und „stille Heldinnen“. Polnische und ukrainische Legionärinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Latzel, Klaus/Maubach, Franka/Satjukow, Silke (Hrsg.): Soldatinnen. Gewalt und Geschlecht im Krieg vom Mittelalter bis heute, Paderborn et al. 2001, 179 (Translation)