"Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

The new military mobilisation led to a system of political coercion in Austria Hungary, which is referred to in the historical literature as "wartime absolutism". This was made possible by several emergency regulations that had already been laid down in the 1867 "December Constitution" in the form of the Emperor's powers to issue emergency decrees, as well as in the right to suspend selected basic rights.

Until the outbreak of the First World War, Austrian parliamentary affairs were dominated by the resistance and conflicts between and within the individual nationalities of the Empire. This impaired the function of the Austrian Reichsrat, which repeatedly led to its proverbial ‘paralysis’, as also happened on 16 March 1914 when the Stürgkh government once again suspended it indefinitely. The war and emergency provisions were therefore issued via what was known as the dictatorship paragraph (Joseph Redlich), Section 14 of the 1867 Staatsgrundgesetz über die Reichsvertretung (Constitution Law on Representation in the Imperial Diet).

On 26 July 1914, i.e. two days before the official declaration of war on Serbia, a special regulation for the state of war entered into effect, the preparation of which dated back to the second half of the 19th century as well as to 1912 (Enactment of emergency provisions in the event of war). Through these special provisions the right to personal freedom and the rights of assembly and association were suspended. In addition, postal secrecy, the inviolability of the home as well as the freedom of speech and of the press were suspended. At the same time, the jury courts in all the countries of the Austrian half of the Empire were abolished, civil persons in certain areas and certain cases subjected to the jurisdiction of the military courts and all industrial enterprises of importance to the war in the Austrian half of the Empire placed under the "War Effort Act" of 1912. In this way, they were subordinated to military leadership and their employees placed under military disciplinary and penal jurisdiction.

According to historian Hans Hautmann, the emergency provisions of the Habsburg Monarchy went furthest amongst those of the warring nations. For the population, the state of emergency meant above all considerable restrictions of their personal rights and general civic rights, which were subordinated to military objectives.

Translation: David Wright

Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005

Hautmann, Hans: Kriegsgesetze und Militärjustiz in der österreichischen Reichshälfte 1914-1918, in: Weinzierl, Erika/Stadler, Karl R. (Hrsg.): Justiz und Zeitgeschichte, Wien 1977, 101-122

Kuprian, Hermann J.W.: Warfare–Welfare. Gesellschaft, Politik und Militarisierung in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges. In: Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig/Hermann J.W. Kuprian/Gunda Barth-Scalmani (Hrsg.): Ein Krieg–zwei Schützengräben. Österreich–Italien und der Erste Weltkrieg in den Dolomiten 1915-1918, Innsbruck/Bozen 2005, 165-177

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Quotes:

„dictatorship paragraph“: Joseph Redlich: Österreichische Regierung und Verwaltung im Weltkriege, Wien 1928, 113, zitiert nach: Hautmann, Hans: Kriegsgesetze und Militärjustiz in der österreichischen Reichshälfte 1914-1918, in: Weinzierl, Erika/Stadler, Karl R. (Hrsg.): Justiz und Zeitgeschichte, Wien 1977, 102

„[...] went furthest amongst those …“: Hautmann, Hans: Kriegsgesetze und Militärjustiz in der österreichischen Reichshälfte 1914-1918, in: Weinzierl, Erika/Stadler, Karl R. (Hrsg.): Justiz und Zeitgeschichte, Wien 1977, 105

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

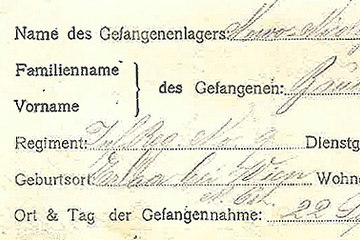

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"