On 25 July 1914, “a regulation of the ministries of the interior and justice explicitly banned the publication of military news in print”.

Further regulations were intended to monitor publications issued in enemy countries, with the import of periodicals being generally prohibited while non-periodical publications were required to be submitted to the competent provincial or police authority for inspection. All newspapers from neutral foreign countries were censored by the police.

These extensive regulations “were noted with increasing concern” in allied and neutral countries, and above all journalists within the Empire soon raised vociferous complaints and criticism of the existing situation. The censorship bodies, they argued, did not act equally with respect to the individual publications, worked slowly and frequently suppressed insignificant content completely arbitrarily. A further bone of contention for domestic journalists was the more moderate censorship in Hungary and the German Reich. There were rumours that the German press was being sent official war news from Austria and that its publications provided more information about Austro-Hungarian operations than the Austrian press.

The notorious blank spaces that were scattered throughout the newspapers had an increasingly counter-productive effect in terms of the official propaganda efforts. The blank spaces left readers with the impression that the news printed by no means corresponded with the whole truth; what was cut out was left to their imagination. This policy of non-information led to the spread of rumours, with at times the most unbelievable content.

The Arbeiterinnen-Zeitung, the social democratic women's newspaper, was permitted during the war but its issues were full of confiscated items. This led the publishers, according to Maureen Healy, to fill the blanks with comments about and for the censors, which, strangely, as the historian has noted, were not censored. One of these blanks on 22 August 1916 was ‘filled’ as follows: "The proposed editorial for this issue has been confiscated in its entirety. To prevent delays to the publication of the newspaper, we had no choice but to waive the possibility of providing another editorial – which would perhaps again have fallen victim to the censor. Comrades! We assure you that your newspaper will not fail to give expression to what corresponds to the desires of all women, but there are powers against which ours are insufficient. Be all the more loyal to your newspaper. One day, finally, it will have to change."

Translation: David Wright

Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, 2. Auflage, Cambridge/New York 2006

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Quotes:

„a regulation of the ministries ...“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 48

„Further regulations were intended ...“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 49-50

„were noted with increasing concern“: quoted from: Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005, 76

„There were rumours …“: Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005, 76

„This led the publishers …“: Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, 2. Auflage, Cambridge/New York 2006, 133

„The proposed editorial ...“: Arbeiterinnen-Zeitung. Sozialdemokratisches Organ für Frauen und Mädchen, 22.08.1916, quoted from: Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, 2. Auflage, Cambridge/New York 2006, 133

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

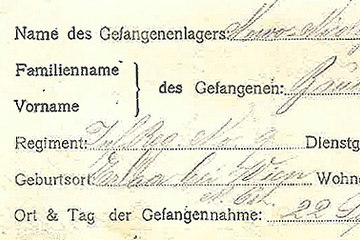

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"