Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

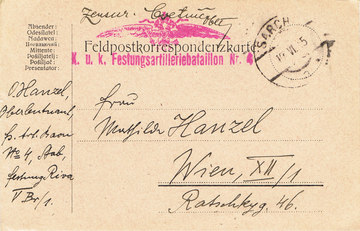

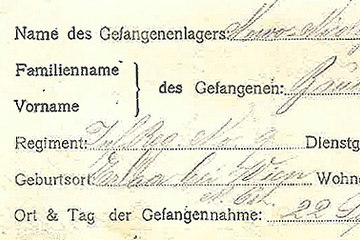

The censorship of letters covered all correspondence sent to and from abroad, (random samples of) domestic correspondence, and initially the entire field post and all letters from prisoners of war.

At the end of 1916, foreign correspondence was sent to “3 major censorship offices in Vienna, Feldkirch and Budapest” where, according to Gustav Spann, “around 1,000 people processed between one and three million post items each month”. The censorship of domestic correspondence was based on random sampling, with the exception of the military areas (for example South Tyrol, southern Styria, Dalmatia), where the censorship was primarily a matter for the senior army command and carried out by Military Censorship Commissions, which were under the authority of the competent military command.

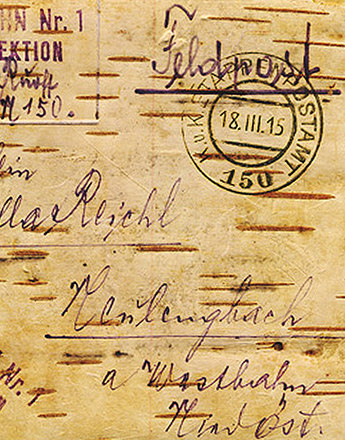

The censorship of the field post was the responsibility of the relevant army commands in the field, while the correspondence of prisoners of war was censored by the Censorship Group of the Joint Central Evidence Office.

The basic principle of the censorship of the field post was that anyone in the army in the field was made responsible for any news from their private correspondence becoming public, even if unintentionally. The use of writing that was ‘unusual’ and hence difficult to read and monitor, such as Gabelsberger shorthand, was forbidden. Nor should there be any indication in a field post letter about the location of the writer or the place where the letter was posted. Above all, however, it was forbidden to send any military or tactical information.

The field post censorship staff were therefore required to prevent any news that conflicted with state and particularly military interests. In practice, this was accomplished by an officer who monitored the collected post. In addition, the letters were to be unsealed. This initially total censorship had to be abandoned by end of 1914 in the light of the huge quantity of post. From 1915, sealed letters could be sent as well. Only random checks were made then, but at the same time “strict penalties were threatened against infringements of the field post regulations”.

Translation: David Wright

Clement Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II 1914-1918 (Graz 1964)

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-165

Quotes:

„3 major censorship offices ...“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149

„around 1,000 people processed …“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-150

„The basic principle of the censorship …“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 122

„strict penalties were threatened …“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 122

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"