Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"

-

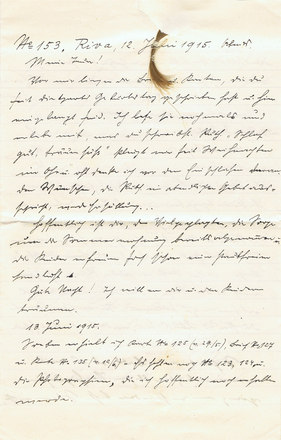

Prisoners of war postcard from Russian war captivity, 1917, page 1

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

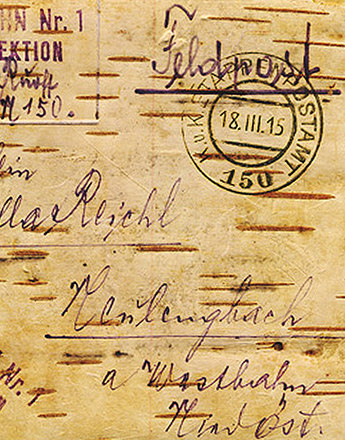

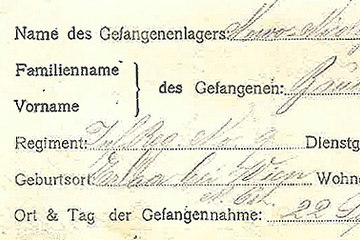

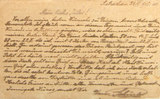

Prisoners of war postcard from Russian war captivity, 1917, page 2

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Shortly after the war began, soldiers on the front developed a number of strategies to get round the censor.

For instance letters were given to comrades who were going on "home leave" from the front. They could then mail the letters at a state post office in the hinterland, thus escaping the censor's hands. It was particularly in such secret letters that soldiers often wrote about matters that they did not dare to set out in letters or cards mailed openly. In some cases, the soldiers also used special codes, as explained by First Lieutenant Ottokar Hanzel in this letter to his wife on 26 June 1915: "The following for the future: I will not underline anything in my messages. If anything is underlined, the opposite is true. Sections in brackets in my messages will be toned down as compared with reality."

Since the writers of field postcards and letters were aware of the censorship, they usually kept back problematic content as well as personal or intimate matters.

The new experiences and events of the war, the ever-present violence, suffering and death, were very difficult to put into letters. In addition, the writers did not want to impose on their recipients the concerns, fears and suffering at the front, and so mostly left out these aspects.

At the same time, there is no doubt that the field post letters from the First World War occasionally contained expressions of discontent about the censors and ‘undesirable content’. A number of those who did this in their letters also addressed comments to the censors directly.

For instance an Austrian soldier, who was wounded in 1916, abandoned by his battalion and fell into Russian captivity. In a letter to his fiancée in June 1917, he openly described how he was wounded and then captured, casting a poor light on his own comrades and the solidarity in his battalion. At the end of the letter, the writer then addressed the following lines to the Imperial and Royal Censorship staff: "This letter has become almost too long. But I appeal to the goodness of the ladies and gentlemen of the censorship office to be lenient, to refrain from demanding a further sacrifice of my sorely-tried patience and to allow these lines to reach my Marie uncut."

Translation: David Wright

Ziemann, Benjamin: Feldpostbriefe und ihre Zensur in den zwei Weltkriegen, in: Beyrer, Klaus/Täubrich, Hans-Christian (Hrsg.): Der Brief. Eine Kulturgeschichte der schriftlichen Kommunikation, Heidelberg 1996, 163-171

Quotes:

„The following for the future ...“ : Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 26.06.1915, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

„This letter has become almost ...“: Anonym to Anonym, June 1917, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 74, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"