-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 22 October 1914, page 2

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 5

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 6

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 7

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 8

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 9

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

-

Mood report by the Imperial-Royal Police Administration Vienna of 6 July 1916, page 10

Copyright: LPD-Wien – Archiv

During the entire war, it was not only the contents of letters that were monitored but also the censors themselves were subject to permanent control. What was known as "hypercensorship" was applied at all censorship offices, “carried out by particularly reliable and experienced censors or by the censorship administration”.

In general, the aim was to use the best trained censors, whose conduct was also morally ‘flawless’ – who for instance did not steal from field post letters. However, “the decisive factor for service as a letter censor was the political ‘qualification’” that was checked when the censorship staff was being selected. The “hypercensors” were after all meant to monitor the work of staff who appeared ‘suspicious’ and “to correct their ‘omissions’”. If objections were raised to the work of a censor, he was noted. Repetitions of such ‘omissions’ could also lead to punishment.

One problem for the correct functioning of the letter censors was the fact that they were regularly assigned to other purposes by the military command. The permanent fluctuations within the individual staff groups firstly had a negative effect on the accuracy of the work and the speed of the censorship offices, since new staff had little experience and were inefficient. At the same time, the regular assignment to other activities had a far from encouraging effect on the trust between the censorship administration and the group under its charge. With time, problems also arose through the lack of censors with appropriate language knowledge, and a lack of qualified staff generally.

As the war continued, the censors were given a further function. The offices responsible had realised that the mail to be checked contained highly useful information about the population and its feelings about the war and the resulting personal situation of the writers of the letters.

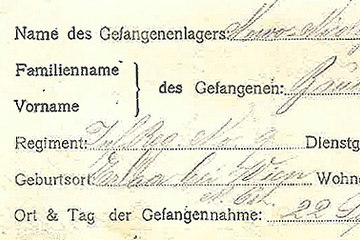

From the end of 1916, therefore, monthly reports were drawn up that were intended to document the effect of specific military, political and economic events on the population of Austria-Hungary, and the ‘reliability’ and ‘loyalty’ of the individual nationalities to the Habsburg Monarchy. In addition, the Censorship Department of the Joint Central Evidence Office, responsible for censoring the correspondence of prisoners of war, drew up “special monthly reports on the situation of the prisoners” – both those of the Empire in ‘enemy’ countries and those of ‘enemy’ prisoners of war in the Empire.

The many quotations from letters were used to make a comprehensive picture of the "mood of the population" within the various nationalities of the Empire. These monthly reports, today kept (incomplete) in the War Archive in Vienna, for instance show that at the end of 1916 people were still confident. But by early 1917, a different mood was observed: confidence had disappeared and been replaced by complaints about hunger, descriptions of the increasing difficulty in obtaining food, comments on social inequality and grievances and the desire for a speedy peace.

Translation: David Wright

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-165

Quotes:

„carried out by particularly reliable ...“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 128

„the decisive factor for service ...‘“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 152

„One problem for the correct functioning …“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 147-148

„From the end of 1916 …“: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 150

„special monthly reports on the situation of the prisoners“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 134

„mood of the population“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 150

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"