Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

-

Censored field post letter, March 1918, page 1

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

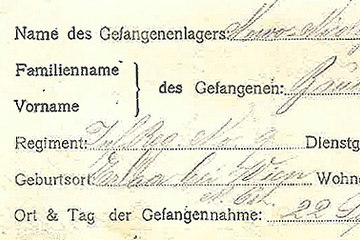

Censored field post letter, March 1918, page 3

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

In order to be able to censor the huge mass of mail, sorting offices were set up after the reform of the letter censorship in 1916, dividing the letters into “language and subject groups”. If there were no objections to a letter, it was stamped by the censor and passed on to the Outgoing Group, from where it was sent to the recipient.

Letters that appeared ‘suspicious’ were sent to the Decoding Group, while those with sections that were to be made illegible were sent to the Remedy Group. Letters that did not appear suitable for transmission for reasons of the content were "inhibited", those with only individual words or sentences that were objectionable were "remedied" (rendered illegible).

In the course of the war, the Remedy Group developed increasingly sophisticated methods for making parts of the text illegible. As stated by Gustav Spann, ink pencils were used at the beginning, but it soon became clear that this approach could easily be reversed using a solvent that removed the censor's ink but had little effect on the letter ink used at the time. As a result, letter ink for instance was only covered with letter ink, and pencil lines with pencil lines. Thus the remedy interventions could no longer be reversed because this would also remove the actual text. An absolutely safe procedure was to cut out entire sentences and text sections with scissors.

Alongside the active interventions in the contents of letters, the letter censors and in particular what were known as the "K Groups" had a further function, namely the active gathering of information. This was carried out above all in the Joint Central Evidence Office, which monitored the correspondence of prisoners of war. The functions of the "Information Service" were on the one hand of a passive nature, since the correspondence of persons suspected of espionage or desertion were subject to strict control and examined in particular for secret writing or hidden messages that had been written in invisible ink. In addition, the "K Group" restored the sections made illegible by the censor in enemy countries.

At the same time, the employees of this service also actively gathered specific information. Thus for instance the censors intervened in the correspondence of persons who appeared suspicious, deserters and defectors in order to obtain information from them without their knowing. For this purpose, use was made of what were known as "imitators", who were able to imitate the writing of the writer in question. According to historian Gustav Spann, such an intervention might for instance be that an amount of money sent to the person concerned would be returned because the address was imprecise. In reply, the censors then usually received the detailed address that they wanted.

Translation: David Wright

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-165

Quotes:

„language and subject groups“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G./Huber, Wolfgang J.A. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 150

„To begin with, ink pencils were used …“ Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 127

„As a result, letter ink …“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 127

„The functions of the Information Service…“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 128-129

„For this purpose, use was made …“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 129

„Such an intervention might for instance …“: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 130

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"