Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

Around the turn of the century, over 2 million people of the Jewish faith lived in the Habsburg Empire. In the age of liberalism, the gradual introduction of legal equality raised their hopes of social integration, while at the same time the emerging anti-Semitism was developing to be a potential threat to the Jewish population.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Jews accounted for roughly 4.5% of the total population of Austria-Hungary. The demographic distribution was extremely uneven, with most living in the north-eastern provinces of Cisleithania and the Hungarian half of the Empire. While hardly any Jews lived in the Alpine regions, the Jewish community in Vienna was one of the largest in Europe.

The Jewish population was highly diverse and can hardly be defined as a homogenous group. Their condition depended on the region of the Empire in which they lived, the extent to which they felt themselves committed to the Jewish faith and how far they had assimilated. The Jews of the Empire did not have a common language, were very differently integrated depending on the regional policies in force and had different experiences in living alongside the non-Jewish population. In this respect, it is difficult to determine a common identity of the Jewish population in the Habsburg Empire. Nevertheless, against the background of the intensifying nationalities conflicts, they were increasingly regarded as an identifiable group.

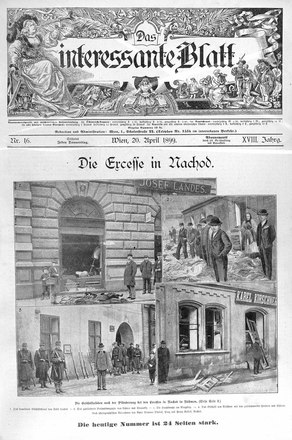

Many liberal Jews had participated in the 1848 Revolution, hoping for the abolition of the existing discrimination. Up into the age of liberalism, the Jewish population of the Habsburg Empire was exposed to strict political and economic discrimination and was socially isolated by means of specific legislation. This discrimination extended from a prohibition on residence, to special fiscal regulations and a restriction of the Jewish population to a small number of professions. In addition, there was an inflammatory hostility that culminated in anti-Jewish riots and violent clashes.

It was only with the rise of political liberalism that a social climate was created in which the emancipation of the Jewish population could advance. An age of progress and tolerance seemed to have begun, and the collapse of the neo-absolutist system in the 1860s brought Jews equal treatment under the law (at different times depending on region). The anti-Jewish restrictions were gradually abandoned, and the abolition of the guilds and the grant of the freedom of trade created the preconditions that made possible the assimilation and emancipation of the Jewish population.

This process of emancipation and integration led to an extensive movement of assimilation within the Jewish population. As the Jewish way of life became more secularised, focussing more on education and becoming more similar to the non-Jewish way of life, large parts of the Jewish population succeeded in establishing themselves in different social fields. They became integrated in the new middle class, pursued liberal professions as lawyers, doctors or actors and were involved in the fields of finance and banking, in industry and in trade.

At the same time, however, a large part of the Jews of the northern and north-eastern parts of the country and the rural areas of the Empire were excluded from the modernisation process. They maintained their Orthodox traditions and as workmen, craftsmen, unskilled labourers or messengers failed to achieve socio-economic advancement.

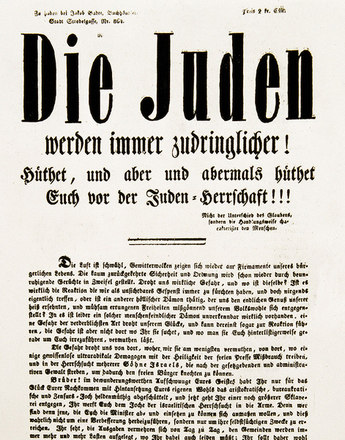

Alongside increasing integration, liberalisation, however, also stimulated anti-Semitism. The anti-Jewish forces gathered within the Roman Catholic Church, while anti-Semitic pamphlets revealed the first signs of a racially-based anti-Semitism and both old and new stereotypes of Jew-hating gained a foothold.

Translation: David Wright

Beller, Steven: Wien und die Juden 1867–1938, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993

Bihl, Wolfdieter, Die Juden in der Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, in: Zur Geschichte der Juden in den östlichen Ländern der Habsburgermonarchie. Studia Judaica Austriaca VIII, Eisenstadt 1980

Häusler, Wolfgang: Toleranz, Emanipation und Antisemitismus. Das österreichische Judentum des bürgerliche Zeitalters (1782–1918), in: Drabek, Anna u.a. (Hrsg.): Das österreichische Judentum. Voraussetzung und Geschichte, München 1988, 83-140

Lichtblau, Albert: Integration, Vernichtungsversuche und Neubeginn. Österreichische jüdische Geschichte 1848 bis zur Gegenwart, in: Brugger, Eveline u.a. (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Wien 2006, 447-566

Rozenblit, Marsha L.: Reconstructing a National Identity. The Jews of Habsburg Austria during World War I, Oxford 2001

Schuster, Frank: Zwischen allen Fronten. Osteuropäische Juden während des Ersten Weltkriegs (1914–1919), Köln/Weimar/Wien 2004

-

Chapters

- Antisemitism: A historical definition

- Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

- Anti-liberalism – anti-capitalism – anti-Semitism

- Antisemitism as a political movement

- "I decide who is a Jew"

- The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

- Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

- The Habsburg Monarchy as the guarantee of pluralistic identities

- Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army

- The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

- The breakdown of the internal peace