The breakdown of the internal peace

The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was regarded by many Habsburg Jews with concern. They welcomed democracy but feared an increase in anti-Semitism. By now they were all too familiar with how rapidly blame could be laid on "the Jews".

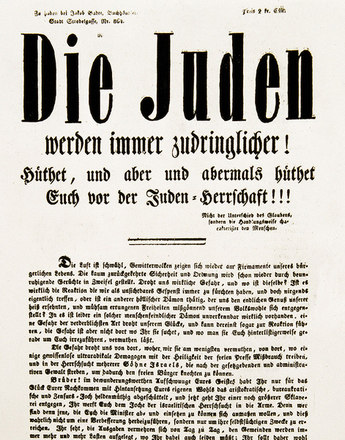

To begin with, the outbreak of the First World War led to an 'internal peace' and a decline in anti-Semitism. However, the unfavourable course of the war and increasing hardship in the home country encouraged an anti-Semitic policy of exclusion. As early as 1917, following the relaxation of the censureship laws, verbal attacks increased in the press. As hopes for victory faded, and as it became more and more difficult to satisfy everyday needs, the anti-Semitic mood increased and the Jewish population was accused of being "war profiteers" and responsible for the misery.

Widespread hostility to the Jews towards the end of the war was, however, not only a reaction to the appalling economic situation but was also fanned by inflammatory campaigns by the political parties. Following the reopening of the Austrian parliament in summer 1917, political anti-Semitism returned to the political agenda and became acceptable in society. The Christian Social Party, the German Nationals and the Pan-Germans demanded the abandonment of the 'internal peace' and focussed their activities on anti-Semitic demagogy. Even the Austrian Social Democrats, previously the only party that had opposed anti-Semitism, was concerned not to be regarded as the defendant of Jewish capital, the liberal press or orthodox Jewry, and mixed anti-capitalist positions with anti-Semitic accusations. Thus the Social Democrats focused on the combination of "patriotic Jews", "Jewish capital" and "bank Jews", and with this confusion contributed to the establishment of the stereotypical rapacious, unprincipled and scheming Jew.

After the collapse of the monarchy, anti-Semitism intensified in Austria. As early as the summer of 1918, there was an increase in anti-Jewish attacks, encouraged by the conservative press, combined with mass demonstrations and violent riots. A core topic of the anti-Semitic agitation and of the electoral campaign for the first national assembly in February 1919 was the Jewish refugees from the eastern part of the Empire. Anti-Semitic groups exploited what was known as the "stab-in-the-back legend", according to which it was not the failure of the army that led to military defeat but rather defeatism on the home front, fomented by Jews and Social Democrats.

Tension between the Jewish population and its surroundings was boosted by associating all unwelcome developments with the bogeyman figure of the Jew. Liberalism was transformed into "Jewish liberalism", the press became the "Jewish press" and the First Republic the "Jewish Republic". The dynamism of the experience of violence, war and defeat increased the population's willingness to regard the "Jewish question" as the solution to the social problems.

Translation: Judith Fritz

Bergmann, Werner/Wyrwar, Ulrich: Antisemitismus in Zentraleuropa. Deutschland, Österreich und die Schweiz vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Darmstadt 2011

Bergmann, Werner: Geschichte des Antisemitismus, München 2002

Pauley, Bruce F.: Politischer Antisemitismus im Wien der Zwischenkriegszeit, in: Botz, Gerhard et al (Hrsg.): Eine zerstörte Kultur. Jüdisches Leben und Antisemitismus in Wien seit dem 19. Jahrhundert, 1990

Pulzer, John: Spezifische Momente und Spielarten des österreichischen und des Wiener Antisemitismus, in: Botz, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Eine zerstörte Kultur. Jüdisches Leben und Antisemitismus in Wien seit dem 19. Jahrhundert, 1990

Rozenblit, Marsha L.: Segregation, Anpassung und Identität der Wiener Juden vor und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard et al (Hrsg.): Eine zerstörte Kultur. Jüdisches Leben und Antisemitismus in Wien seit dem 19. Jahrhundert. 2., neu bearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage, Wien 2002

-

Chapters

- Antisemitism: A historical definition

- Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

- Anti-liberalism – anti-capitalism – anti-Semitism

- Antisemitism as a political movement

- "I decide who is a Jew"

- The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

- Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

- The Habsburg Monarchy as the guarantee of pluralistic identities

- Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army

- The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

- The breakdown of the internal peace