The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

In the Habsburg Empire, the anti-Semitic movement was strongly concentrated on Vienna. Student and craftmen's movements assumed opinion leadership and carried anti-Semitism into the public.

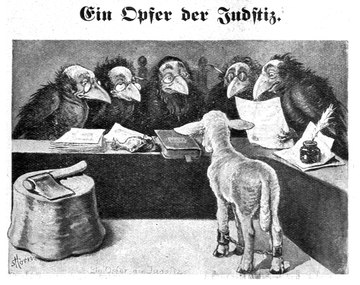

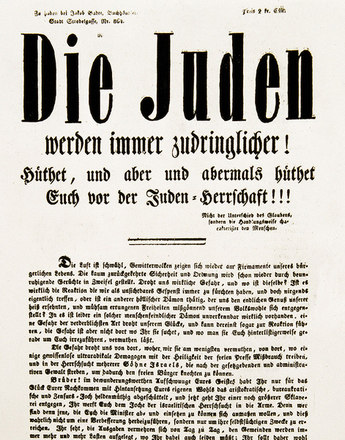

In the Habsburg Empire, parts of the educated middle class were the spokesmen for the anti-Semitic mood and determined the anti-Jewish rhetoric. Its values, attitudes and cultural patterns were permeated with an anti-Semitic ideology that spread to broad circles of the population.

Among students, anti-Semitism met with a particularly strong response. At the Medical Faculty of the University of Vienna, a racially-based anti-Semitism took hold that culminated in demonstrations against Jewish fellow-students. Hatred was stirred up against Jews on posters with the words "Regardless of what the Jew believes, it's his race that makes him a swine".

As early as 1877, Jews were refused membership of the Teutonia fraternity, and a year later the Vienna Libertas fraternity also excluded baptised Jews in order to counter the fear of Vienna University being 'swamped with foreigners'. In other cities of the Empire such as Graz, Innsbruck and Prague, anti-Semitic student movements also formed, later merging to create the Waidhofener Verband in 1896 and adopting the anti-Semitic principles of the German National fraternities in the Waidhofen Resolutions.

At the same time, craftsmen formed to set up anti-Jewish groups and protested against the alleged damage to their business from Jewish competitors. The minor gentry and the middle class also adopted an anti-Jewish position and amongst the peasant class anti-Semitic hatred fell on fertile soil. Farmers were particularly affected by the new market structure and were easy to mobilise. "Profiteering Jews" were made responsible for the commercialisation of agricultural production and related phenomena such as financial dependency on loans and farms falling into debt.

It was only amongst the working class that anti-Semitism was unable to gain a foothold. It regarded an anti-Semitic attitude as an expression of conservativism, and accordingly social democracy adopted the values of liberalism and condemned anti-Semitism as a backward ideology. The hope was that anti-Semitism as a concomitant of the capitalist social structure would sooner or later be overcome by the rise of socialism. In their battle against capitalism, social democrats did not distinguish between Jewish and non-Jewish capital. For this reason, they were defamed by their opponents as the heirs of "Jewish liberalism" and as a "Jewish security unit".

Translation: David Wright

Bergmann, Werner/Wyrwa, Ulrich: Antisemitismus in Zentraleuropa. Deutschland, Österreich und die Schweiz vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Darmstadt 2011

Häusler, Wolfgang: Toleranz, Emanzipation und Antisemitismus. Das österreichische Judentum des bürgerlichen Zeitalters (1782–1918), in: Drabek, Anna et al. (Hrsg.): Das österreichische Judentum. Voraussetzung und Geschichte, München 1988, 83-140

Lichtblau, Albert: Integration, Vernichtungsversuche und Neubeginn. Österreichisch-jüdische Geschichte 1848 bis zur Gegenwart, in: Brugger, Eveline et al. (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Wien 2006, 447-566

Shulamit, Volkov: Jüdisches Leben und Antisemitismus im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, München 1990

-

Chapters

- Antisemitism: A historical definition

- Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

- Anti-liberalism – anti-capitalism – anti-Semitism

- Antisemitism as a political movement

- "I decide who is a Jew"

- The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

- Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

- The Habsburg Monarchy as the guarantee of pluralistic identities

- Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army

- The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

- The breakdown of the internal peace