Men without a History?

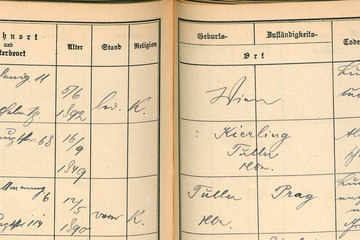

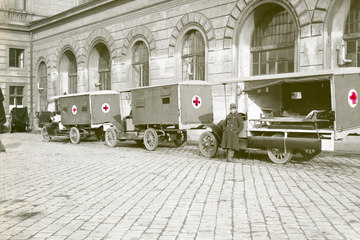

In summer 1914, probably no one in the Habsburg Monarchy could imagine what effects the coming war would have and what measure of suffering it would cause. And probably only very few thought that the “Gang nach Serbien” (the move to Serbia), as a retaliation campaign, would last more than four years, or that during this time, all in all, around eight or nine million men would be mobilised (the statistics diverge in the literature). They make up that anonymous and nameless collective whose everyday life on the fronts of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy has never received sufficient attention. Because until quite recently, with few exceptions, there has been only a laggard attempt to pose questions in Austrian historiography about the everyday experiences, awareness, sense of purpose and interpretations in particular of the normal trooper.