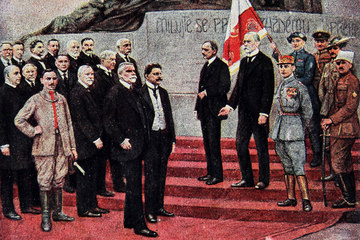

The Founding of Czechoslovakia

While the events in Prague were catapulting the country into a historic new phase, the home team of leaders was in Geneva to discuss further steps towards independence with the general secretary of the exiled Czechoslovakian National Council, Edvard Beneš. It was only by reading the newspapers that these gentlemen first learned that an independent Czechoslovakia had been proclaimed in Prague.