Hamster buying, queuing, do it yourself: individual strategies to provide food become indispensable

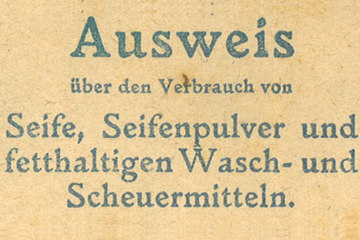

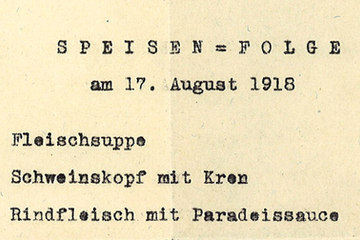

At the beginning of the war the population had mainly to struggle with exorbitant price increases. Indeed the increasing shortages made themselves felt already at the start of 1915. The purchase of everyday articles as well as the production and conservation of food became the predominant tasks.

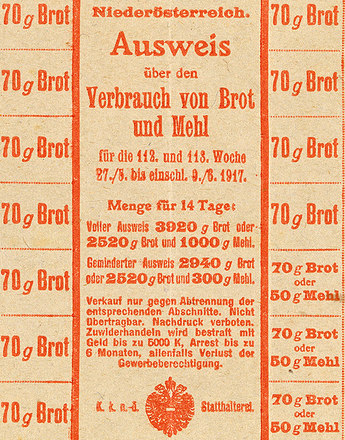

The lack of consumer goods had to compensated for by tighter housework, carried out with skill and considerably more effort. The unpredictability of rationing made it harder to plan the housekeeping; darning, making food stretch, boiling and preserving became skills important for survival.

In this situation of shortages, the civilian population attempted to fend off the worst privations by means of individual consumer strategies. Housework had long since turned into a survival-ensuring activity and housewives had become managers of scarcity. Already in the second year of the war, most goods could only be bought by queuing for hours. Soon hundreds of people stand in line shaped everyday life in the cities. Mostly women and children, but also soldiers on leave, rowed up in the early hours already in food queues formed in front of shops and stands. Thus the Vienna Police Direction observed in reports on February 2, 1916: ‘In general it is observed that queues are increasing. Queues can be noted for almost every important commodity. People often queue up without knowing what is available in the shop, when asked, they reply that they want to buy everything, as they need everything. […] Critical situations occur almost daily after sales of flour have ended in the Large Market Hall in the III District, where people spend almost whole nights outside by waiting for hours.’

The waiting was a fixed element of daily life, for only through stamina and strategic time planning could the chance of getting some of the small quantities of flour, rice and milk be increased. As one’s place in the queue was crucial, with the shortages becoming more acute, hungry and freezing children often stuck it out in front of shops at 2 o’clock in the morning already, so as to be first when the shop opened. Yet frequently the patience of those waiting was tested in vain, and they could be first in the queue and yet the hoped-for goods had already sold out. This was an experience also shared by the 13-year old Anna Stingel, who noted in her diary on October 7, 1916: ‘The food prices have now risen so greatly that we hardly know what to buy. […] What’s more, it’s very hard to get. You have to stand for hours and wait and at the end get nothing at all.’

If those waiting came away empty-handed, scuffling often broke out, interaction between people was dominated by rudeness, and hostilities got the upper hand in relations between customers and traders.

One important means of mustering up food was self-sufficiency. City dwellers who hitherto had been consumers now became active as producers, tending small allotments. On plots of land of around 100 to 300 square metres, fruit and vegetables were planted, rabbits bred and chickens kept. Emperor Karl recognised the importance of self-sufficiency for the survival of the Viennese, and made plots of garden allotments available to the city on the Wasserwiesen land in the Prater. The number of allotments in Vienna alone rose to 157,300 by 1918.

Yet in view of the privations, the population frequently had no other choice than to fall back on the burgeoning black market, and women developed subversive strategies to ensure the survival of their families. This included methods of dealing that exploded the borders laid down by the law, which yet seemed morally legitimate in view of the emergency situation. Hundreds of city dwellers travelled to surrounding villages at the weekends for purchase en masse, and swopped valuable items and natural produce for food. The number of thefts steadily rose, forged food coupons came into circulation, and both the black market and illicit trading turned into economic spaces that safeguarded people’s existence.

The population reacted bitterly to official attempts to prohibit foraging trips and receiving of stolen goods. The state, which had so clearly failed in providing basic provisions, had had its moral right removed to pass judgement on strategies that provided for individual existences. The authorities had to acknowledge that the survival of entire cities could be ensured only through the existence of a parallel economy.

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich, 1978, 661-682

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004

Daniel, Ute: Arbeiterfrauen in der Kriegsgesellschaft. Beruf, Familie und Politik im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 1989

Quotes:

„Im allgemeinen wird beobachtet...“: Stimmungsberichte aus der Kriegszeit, k. k. Polizeidirektion Wien, 2. Februar 1916, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

„Es bestehen jetzt so große Lebensmitteltheuerungen...“: Anna Hörmann, Tagebuchaufzeichnung, Dokumentation lebensgeschichtlicher Aufzeichnungen, Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte der Universität Wien