The food emergency in the First World War as a key social problem

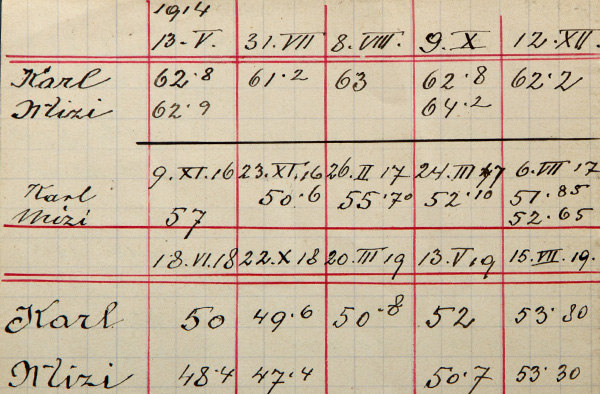

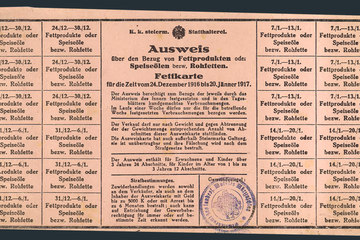

On the ‘home front’, the consequences of the supply crisis were among the most deeply felt of all the war year experiences. Although the government had already reacted in 1914 to the first supply shortfalls with intervention measures, yet did not succeed in getting a grip on the food situation in the long run. A key factor in this was the misjudgement of the military balance of power, the assumption arising from it of a short war and a fatal mismanagement on the part of the authorities. Now the civilian population was called upon to balance out the state inadequacies with individual supply strategies. Foraging trips to the countryside, night-long queuing and a burgeoning black market became core elements in an economy of shortages and emergencies that threatened their very existence.

In the final years of the war, the food emergency worsened markedly, turning into the combustion point both socially and politically. The insufficient provision of basic foodstuffs led to social tension. The government was accused of inefficiency and unjust distribution, the search for the ‘enemy within’ threatened the social cohesion of the civilian population. Hunger and mistrust towards the state drove people on to the streets. The question of food supply set off a dynamic which culminated in the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.