Searching for the ‘enemy within’

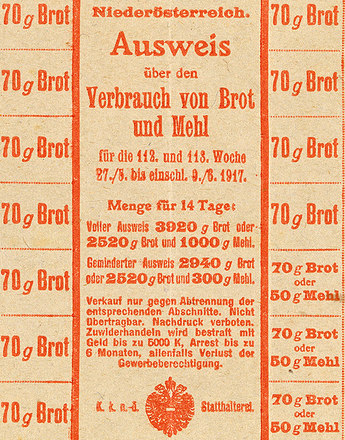

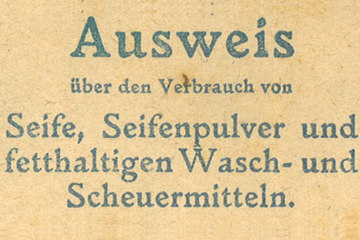

The third war winter became the turning point. In view of the continuous price rises and shortages, the population’s willingness to make sacrifices reached its limits. The catastrophic hunger threatened the internal cohesion of the society, social chasms grew deeper and the search for those to blame began.

In the autumn of 1916 the atmosphere shifted in the population. Stocks were used up, urgently anticipated imports from Rumania failed to materialise, and the optimistic belief that the war could be endured safely faded. Hunger and the food crisis became the overriding theme, pushing any interest in the course of the war and reports from the front in the background.

The waiting queues at markets, in front of shops and offices were the social melting-pot in which rumours swirled, information was exchanged and opinions aired. Women listened out and reported on what was on offer at markets. All were affected by the queuing and people came into contacts with others who they would have scarcely met during peacetime.

The increasing shortages led to the loss of solidarity between those waiting, however. Under-nourished and exhausted people reacted irritably towards one another, human interaction became coarser. Meticulous attention was paid to maintaining the unwritten laws of queuing. The readiness to accept special roles (for example, that of the pregnant, elderly or frail person) disappeared and fighting broke out daily. The all-consuming misery resulted in social taboos disappearing and civilised understanding collapsing.

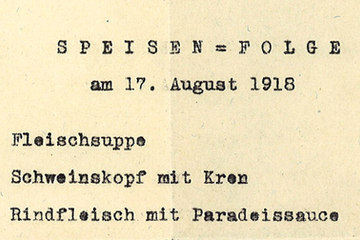

When the shortages could no longer be made up for by cautious housekeeping, the (civilian) population increasingly saw itself as a victim of the war. State propaganda was at pains to depict the enemy states as the cause of the emergency, so as to keep the truce. Yet the search was on to find those who were guilty in their own ranks. Tensions were released along social lines and various social groupings were held responsible for the misery. The atmosphere was stoked further by the extreme injustice of the emergency was spread out. The upper middle classes were able to compensate relatively easily for the shortage of provisions in the first two years of the war, and could still acquire goods in sufficient amounts on the black market even towards the end of the war for expensive money; the less well-off segments of society, in contrast, suffered sheer privation and struggled with the grave consequences of malnutrition.

Yet social fissures ran, not only between the working and the middle classes, but also between agricultural producers and urban consumers, who were strained by the food crisis. Due to the continuously rising food costs, the city population felt at a disadvantage in comparison with the farmers. Rumours spread about extortionate farmers who profited from the misery and filled their stables to the ceilings with the splendour of the cities. Moreover, a moral crisis of the middle class occurred, whose living standards suffered under the hardship of war and who had to accept that consumer goods that had once been considered precious, had now lost importance in view of food prices.

Buyers spied on one another and blamed the dealers for pushing up prices by holding back goods, and so acting contrary to the common good. Landowners and wholesalers were criticised for selling on products with great profit, and for profiting from the misery of the people. Black marketeers, speculators and war profiteers became Public Enemy Number One.

Newspapers propagated the stereotype of the Jewish war profiteer and neighbours and traders denounced each other with the reproach that the other was hoarding vast amounts of food. Affected by complete exhaustion, social cohesiveness threaten to implode. The basis of all hostilities was the impression that the burden of the war was unevenly spread. Rumours circulated that the food crisis was not just due to exports falling and harvest failing; unfair distribution was also seen as a cause.

Berger, Peter: Die Stadt und der Krieg. Wiens Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 1914–1918, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 211-219

Davis, Belinda: Heimatfront. Ernährung, Politik und Frauenalltag im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Hagemann, Karen/Schüler-Springorum, Stefanie: Heimat – Front. Militär und Geschlechterverhältnisse im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Frankfurt/New York 2002, 128-149

Healy, Maureen: Am Pranger. Auf der Suche nach den Schuldigen, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 190-197

Healy, Maureen: Eine Stadt, in der sich täglich hundertausende Anstellen, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 151-157

Healy, Maureen: Vom Ende des Durchhaltens, in:Alfred Pfoser, Andreas Weigl (Hg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg. Wien 2013, 132-139

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004