On stretching, diluting and thinning

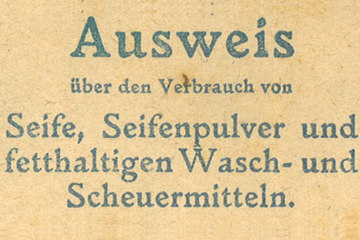

To compensate for bottlenecks in the provision of basics, improvisation was in demand. All manner of substitutes featured in the kitchens of the Monarchy, and became a symbol of a failure to provide basic services.

Marked by the escalating supply emergency, the parameters of what was designated as foodstuffs was constantly broadened. The miserable conditions forced the population not only to limit their familiar diet, but also to extend to include a whole new range of foods. The skill at making the hitherto unpalatable tasty became a feature of existence.

War cookery books appeared on the market with titles that were unambiguous in their tenor: ‘Frugal Cooking’, ‘It Must Suffice! Feeding the People Economically as a Condition of Victory’ and ‘Little Cook Book in Times of Need’ contained practical tips and tricks, passing on knowledge to compensate for the scarcities. Frugality rose to become the catchphrase of the day, and the guidelines of ‘patriotic housekeeping’ integrated those it addressed into the economic war being waged. The exhibition held in the Prater in 1918 on substitutes was comprehensively devoted to the subject of surrogates, presenting various products designed to compensate. Moreover, posters called the population to join in collecting campaigns, so to jointly amass raw materials for the purposes of compensating: ‘Especially those circles not occupied with agricultural work fulfil a patriotic duty when they gather as much as possible of the rampantly growing foodstuffs and animal feeds. Big and small, old and young, all participate in the collection, in order where possible to alleviate the endurance of the following winter.’

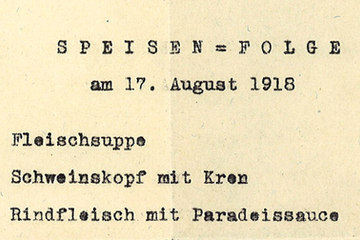

High-quality food was diluted with lower-quality, and rubbish tested for its recyclability. Potatoes were used as substitutes for flour, in meat dishes and in the form of puddings and sausages. When even potatoes became rare due to bad harvests, turnips served as a surrogate for the surrogate. Dried fruit took the place of fresh vegetables and already in October 1914 wheat and rye breads were replaced by barley, maize and potatoes. The so-called ‘war bread’ consisted of a mix of lower-quality flour varieties, its beans and grasses blended. In 1918 this consisted almost exclusively of cornmeal and the ‘maize ghost’ became a metaphor for the catastrophic food conditions.

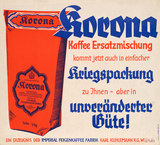

Ersatz coffee was made from chicory or acorns, and there were 70 various diluting mixtures for tobacco alone, mostly a combination of tobacco, beech foliage and hops. In 1915 the so-called ‘war sausage’ consisted for one third each for potatoes, blood albumin (a meat substitute) and inferior-quality meat wastes. The decree of two meatless days a week in May of the same year struck many as ironic, given that meat had long since ceased to be a daily matter of course due to import tariffs and mass purchasing by the military authorities.

Oils were pressed from fruit cores, horse-chestnuts and beech-nuts. To extract fats, people made use of bones and cadavers, constructing fat-filters in the wastewater pipes of restaurants. When the privation could barely be dealt with any more and housework had long since become survival work, one tried to quench the worst of the hunger pains with wild herbs, roots and grasses.

But not only the lack of nutritious food was problematic, but also the inferior quality of the substitute products. Flour varieties were frequently infested with moths or corn weevils, bread made of worthless flour soon turned to mould and was unpalatable. Yet in view of the acute shortage, even surrogate with hardly any nutrition, and foods that were stretched to the point of being unrecognisable, were flogged for horrendous prices. Moreover, traders attempted to profit from the misery and launched surrogates on the market which consisted of barely more than colour additives and cellulose, and which were not worthless but a risk to health, too.

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard u.a. (Hg.): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich, 1978, 661-682

Mertens, Christian: Die Auswirkungen des Ersten Weltkriegs auf die Ernährung Wien, in: Pfoser,Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 162-171

Quotes:

„Besonders jene Kreise...“: Merkblatt über das Sammeln und die Verwertung von Waldfrüchten, Futtermittelzentrale Wien, vermutlich 1916, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Signatur: KS 16215537