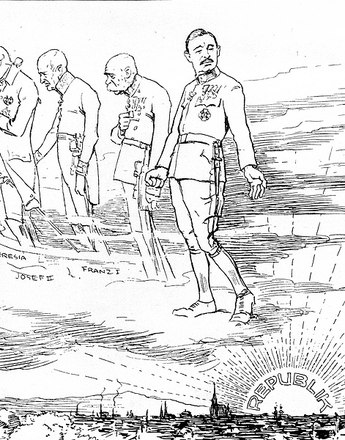

The death of Franz Joseph was no surprise, but for the Habsburg Monarchy it meant the loss of a major symbolic figure. The succession was exploited as propaganda before the war-fatigued population as the sign of a new era.

This hope was also stage-managed deliberately in the choreography of Franz Joseph’s funeral, when the young imperial couple Karl and Zita followed the coffin. Holding the hands of his parents was the four-year-old Crown Prince Otto – dressed in dazzling white in the midst of the completely black funeral cortège – as symbol of a hopeful future for the dynasty.

In Karl a new generation took over at the moribund Viennese court, a generation that had a different approach to the Habsburg traditions. The differences were evident in the way Karl behaved with those around him. Franz Joseph had always been very aloof: concerned to preserve the dignity of his majestic office, he put a clear distance between himself and the rest of humanity, never engaging in any personal discourse or asking for advice. He listened to the opinion of various advisors and then issued his irrevocable decision. By contrast, Karl cultivated a far more personal and cooperative tone in his dealings with other people, a trait that was often interpreted as weakness.

On the other hand, Karl acted in a personable, sympathetic way and cultivated an informal style of behaviour. Many details of antiquated etiquette were abandoned: for instance, Karl greeted people with a hand-shake, and those at his audiences were invited to sit down, which would have been inconceivable with Franz Joseph. It communicated a different image as a ruler: while still alive Franz Joseph became a petrified monument to himself; Karl, inspired by a strong feeling of dynastic mission, relied on charisma – which apparently he did not always possess. The old emperor was unapproachable and other-worldly, while Karl wanted to live in the here and now, which made him all the more vulnerable.

Karl was also the child of another time and had a more open approach to modern technology: in contrast to Franz Joseph telephone, automobile and other signs of the modern age were self-evident parts of his everyday life. Karl was also used to a different speed in decision-making, which earned him the derisive nickname “Karl all of a sudden.”

Many of his ad-hoc decisions indeed showed inconsistency and irresolution. Karl was bubbling with ideas but found no opportunity to realise them, because in his naiveté and inexperience he frequently lost his way in the established corridors of power and the realpolitik of the Monarchy.

The young monarch was also regarded as easily led and subject to the influence of his wife Zita and a circle of intimates and friends that began to form around him. He also frequently ignored the opinion of official advisors and experts.

One of the leading figures who had doubts about Karl’s suitability as monarch was Ernest von Koerber, who served briefly as prime minister of Austria-Hungary at the time of the succession. Appointed to this office by Franz Joseph in October 1916 shortly before the latter’s death, Koerber resigned in December of the same year due to massive differences of opinion with the new emperor. Koerber’s assessment of the situation was wholly without illusion: “The old emperor laboured for sixty years to bring about the fall of the monarchy; the young one will manage it in two years”.

He was to be proved right …

Translation: Sophie Kidd/Abigail Prohaska

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Um Krone und Reich. Die Tragödie des letzten Habsburgerkaisers, Wien 1968

Broucek, Peter: Karl I. (IV.). Der politische Weg des letzten Herrschers der Donaumonarchie, Wien 1997

Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. „Selig, die Frieden stiften …“. Die Biographie, Wien 2004

Gottsmann, Andreas (Hrsg.): Karl I. (IV.), der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2007

Leidinger, Hannes; Moritz, Verena; Schippler, Berndt: Schwarzbuch der Habsburger. Die unrühmliche Geschichte eines Herrscherhauses, 2. Auflage, Innsbruck, Wien 2010

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

-

Chapters

- Franz Joseph: the ageing emperor

- The problem of the succession

- Franz Joseph and Franz Ferdinand – a tense relationship

- Franz Ferdinand and his political programme

- Kaiser Wilhelm II: The Beloved Enemy

- “Archduke Bumbsti”

- Karl as successor to the throne

- The New Emperor

- Karl I and the collapse of the Monarchy

- The last days of the Monarchy

- Emperor Karl on his way into exile