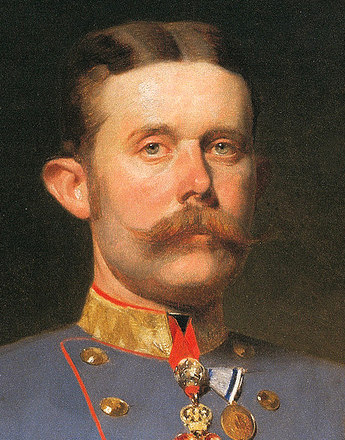

The successor to the throne recognised the problems besetting the Habsburg Monarchy in all clarity. He believed the solution would be to accentuate centralism and an authoritarian style of rule. His rule – had he ever ascended the throne – would have meant a conspicuous step backwards for the political agenda of democracy.

Franz Ferdinand was a fervent advocate of the monarchic principle, according to which it was the ruler’s right to have a pre-eminent position in the political system of the Monarchy. As future emperor, he saw himself as an autocrat, whose word would have the most decisive influence.

Also fitting into this concept was his resolute advocacy of a reinforced central state, to which, in the spirit of “Greater Austria”, the demands of the individual nationalities should be subordinated. Not a very tactful person, Franz Ferdinand made no effort to hide his deeply-felt denial of Austria-Hungarian dualism; in his opinion it was the root of all evil: “This arrangement is the greatest misfortune: wrenched out of the Emperor after the disaster in ’66 (= Battle of Königgrätz), it is crippling us economically and besides, this dualism is the very ruin of the Monarchy. It cries to heaven, what these Magyars are up to!” Because of his undisguised animosity against the Hungarian cause, Budapest regarded him as an enemy.

In this question Franz Ferdinand was in conspicuous opposition to Franz Joseph. The crown prince made a start by propagating plans for a form of trialism through an agreement with the South Slavs, whose settlement regions would become a third part-state of the Monarchy under Croatian leadership. The aim was to channel the South Slav tendencies towards unity and to neutralise Serbia’s role as unifier of the Slav peoples in the Balkans. A further inner-political effect would be to dampen Magyar separatism. Furthermore, the dynasty would be able to assume the role of a dominant central power in a tripartite state.

Later, the successor to the throne distanced himself from this plan and increasingly favoured a conspicuously centralist re-organisation of the Monarchy. The Programme for the Succession published in 1911 offered a kind of overall survey of the political concepts gleaned from the circle of Franz Ferdinand’s advisers: the decisive phase would be the time between the assumption of power after the old emperor’s death and Franz Ferdinand’s coronation as King of Hungary. The reforms aiming to hollow out the dualist arrangement would be executed immediately at his accession but prior to the coronation, because the coronation oath bound the king to the constitution, which would have cemented the status quo in Hungary.

One reform measure envisioned the introduction of universal franchise in Hungary in order to break the supremacy of the Magyar elite. It was thought in Franz Ferdinand’s circle that these disputes about nationality would lame the Hungarian Parliament exactly as had happened in the Austrian Imperial Council. The restructuring of the constitution was tantamount to a coup d’état and designed to bring about a massive weakening of Hungarian autonomy within the totality of the State. In a state of emergency any resistance or even a potential civil war would be crushed using violence through military action. The objective was a reinforcement of the central power, and the Dual Monarchy would be replaced by a unified state with distinct emphasis on the German element – comparable with the Austrian Empire before the revolution of 1848. This programme, itself hazarding the consequences of an authoritarian coup d’état, eloquently expresses the idiosyncratic mixture of reactionary conservatism and reform zeal typical of Franz Ferdinand.

In foreign affairs Franz Ferdinand was an opponent of war policy as advocated by the Chief of the Austrian General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf. The successor to the throne was quite aware of the Monarchy’s weakness. As General Inspector of the total armed forces (since 1913) – and thus in the event of war Supreme Commander in proxy of the aged Franz Josef – he availed of profound insights into the military potential of the Dual Monarchy. Franz Ferdinand was sufficiently realist to comprehend that the Habsburg Empire would not survive a major military conflict.

Above all, the impending conflict with Russia was in his opinion urgently to be avoided. Franz Ferdinand pursued a policy of rapprochement with the Tsarist Empire, in which he considered himself to be a partner in the struggle against nationalist extremism in Southeast Europe. The goal was to be a marriage of convenience of two authoritarian regimes, because “a war between Austria and Russia would end either with the fall of the Romanovs or with the fall of the Habsburgs – perhaps both.”

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Aichelburg, Wladimir: Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este und Artstetten, Wien 2000

Bled, Jean-Paul: Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger, Wien u. a. 2013

Holler, Gerd: Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Wien [u.a.] 1982

Kann, Robert A.: Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand. Studien, Wien 1976

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Schippler, Bernd: Schwarzbuch der Habsburger. Die unrühmliche Geschichte eines Herrscherhauses (2. Auflage, ungekürzte Taschenbuchausgabe), Innsbruck [u.a.] 2010

Quotations:

“This arrangement is the greatest misfortune ...“ Franz Ferdinand, quoted from: Jean-Paul Bled: Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger, Wien u. a. 2013, 125

“a war between Austria and Russia ...“, Franz Ferdinand, quoted from: Jean-Paul Bled: Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger, Wien u. a. 2013, 240

-

Chapters

- Franz Joseph: the ageing emperor

- The problem of the succession

- Franz Joseph and Franz Ferdinand – a tense relationship

- Franz Ferdinand and his political programme

- Kaiser Wilhelm II: The Beloved Enemy

- “Archduke Bumbsti”

- Karl as successor to the throne

- The New Emperor

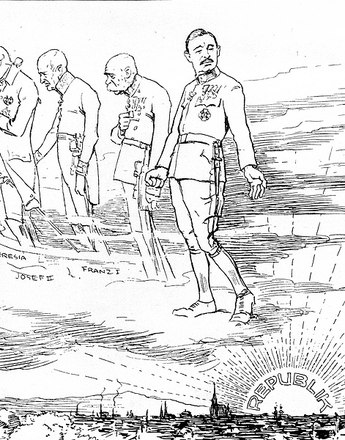

- Karl I and the collapse of the Monarchy

- The last days of the Monarchy

- Emperor Karl on his way into exile