Towards the end of the century the term ‘Fortwursteln’ (‘muddling through’) was coined to describe Emperor Franz Joseph’s policies. The political decision-makers saw no possibility of finding solutions for the pressing problems that beset the Monarchy on all sides.

A major critic of the ossification of the political system that had taken place under Franz Joseph was his son Rudolf, whose supported liberal ideas and who was deliberately kept at arm’s length from any political influence. There were also significant differences of opinion, additionally fuelled by personal dislike, between Franz Joseph and his nephew Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who had been chosen as his successor after Rudolf’s suicide.

From 1893 the governments of the Austrian half of the empire became increasingly unstable, foundering successively on their attempts to solve urgent social problems and coming under sustained pressure from nationalist extremists. The army and the bureaucracy thus became the most important pillars of the Monarchy, which continued to be administered according to antiquated principles without any attempt at basic remediation of its shortcomings. The empire and its ruler were overwhelmed by the modern age. ‘The old gentleman in Schönbrunn’ kept himself out of day-to-day politics and as he aged became a mythical symbolic figure beyond all criticism who held the Monarchy together. It was not state patriotism that was propagated as the expression of citizens’ allegiance to the Monarchy but their loyalty to the monarch.

In addition, the situation in the Balkans, the ‘powder keg of Europe’, was developing to the disadvantage of Austria-Hungary. When Bosnia-Herzegovina was finally annexed by Austria in 1908, a foreign policy crisis erupted between the Habsburg Empire and Serbia and the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, room for manoeuvre in the foreign policy arena was very limited as Austria-Hungary had no allies in Europe apart from Germany, making her all the more dependent upon her only partner.

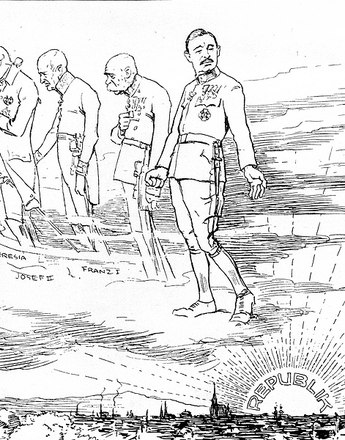

Tensions were already running at dangerous levels when news broke of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand and his wife at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Franz Joseph regarded this act as an attack on the honour of the dynasty and declared war on Serbia, whom he saw as having masterminded the assassination. In a kind of chain reaction one state declared war upon another and the First World War began. The role played by Franz Joseph in all this has been judged in various ways by his biographers. Some portray him as a senile dotard who, isolated from the world around him, no longer grasped the consequences of his actions. Others believe the elderly emperor led his empire to its doom with his eyes open, having seen the end coming for the world he was familiar with, citing Franz Joseph’s well-known dictum as evidence of his fatalism: ‘If we really have to go under, then we should at least go decently!’

Franz Joseph died of pneumonia at the age of 86 on 21 November 1916 amid the turmoil of the First World War. With his death the Monarchy had lost one of the last linchpins holding together the heterogeneous structure of the state which had in any case been weakened by social and ethnic tensions and was now being tested to the limit by the demands of global conflict. For many, the funeral procession on 30 November 1916 was a memorable symbol for the end of an era.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Beller, Steven: Franz Joseph. Eine Biographie, Wien 1997

Herre, Franz: Kaiser Franz Joseph von Österreich. Sein Leben – seine Zeit, Köln 1978

Katalog: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs – 2. Teil: 1880–1916. Glanz und Elend. Niederösterreichische Landesausstellung auf Schloss Grafenegg 1987, Wien 1987

Leidinger, Hannes / Moritz, Verena / Schippler, Bernd: Schwarzbuch der Habsburger. Die unrühmliche Geschichte eines Herrscherhauses, Innsbruck/Wien 2010 (2. Auflage)

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie (= Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hg. von Herwig Wolfram), Wien 2005

Unterreiner, Katrin: Kaiser Franz Joseph. 1830–1916. Mythos und Wahrheit, Wien 2006

Winkelhofer, Martina: „viribus unitis“. Der Kaiser und sein Hof. Ein neues Franz-Joseph-Bild, Wien 2008

-

Chapters

- Franz Joseph: the ageing emperor

- The problem of the succession

- Franz Joseph and Franz Ferdinand – a tense relationship

- Franz Ferdinand and his political programme

- Kaiser Wilhelm II: The Beloved Enemy

- “Archduke Bumbsti”

- Karl as successor to the throne

- The New Emperor

- Karl I and the collapse of the Monarchy

- The last days of the Monarchy

- Emperor Karl on his way into exile