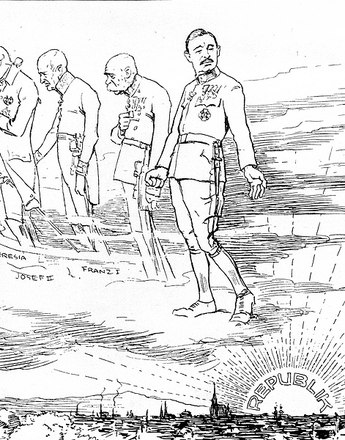

The Habsburgs in exile I: from Switzerland to Madeira

In March 1919, on the initiative of the British government, preparations were started to enable the imperial family to leave the country and go into exile. It was felt that Karl’s continued presence in Austria was helping to destabilize conditions in the country.

Deprived of power since signing the document in which he renounced all participation in the affairs of state on 11 November 1918, Karl had taken up residence with his family at Schloss Eckartsau, an imperial hunting lodge in the Marchfeld region of Lower Austria. On 23 March 1919, Karl and Zita, together with their children and a small entourage, boarded the train for Switzerland, which after lengthy negotiations had declared itself willing to accept the former emperor.

On the day after their arrival in Switzerland the imperial couple took up quarters in Schloss Wartegg near Rorschach, which was situated on Lake Constance within sight of Austria and belonged to relatives of Empress Zita. By May they had moved to the Villa Prangins on Lake Geneva. The Swiss government had insisted that the exiled imperial family move their place of residence to the west of the country, away from the Austrian border.

A small court household in exile formed around Karl and Zita, consisting of the former court bishop Seydl, the aides-de-camp Count Wladimir Ledochowski and Zeno von Schonta together with the secretary Karl von Werkmann. Zita was accompanied by her lady-in-waiting Countess Gabrielle Bellegarde and the children’s governess, Therese von Kerssenbrock. Karl’s mother, Archduchess Maria Josefa, also followed the imperial couple into exile.

In Zita’s memoirs – in which the former empress gives a very one-sided and subjective account of the events surrounding the collapse of the Monarchy – their stay at Prangins is described as a time of relaxation after all the strain of the preceding months. However, Prangins was also the scene of clandestine preparations for an attempt to regain power in Hungary.

After Karl’s two failed attempts at a putsch in Hungary, the Western powers decided in November 1921 that the continued presence in Europe of the former emperor was no longer politically tenable. Together with their family the couple were put on board the British cruiser HMS Cardiff, which was to take them to a place far away from Europe. Not even the crew knew the destination of the voyage. Once at sea, the captain received the order to take Karl and his family to Madeira, an island in the Atlantic under Portuguese sovereignty.

At first the family took up residence at Reid’s Palace Hotel in Funchal, the capital city of the island. However, they were soon unable to afford this highly fashionable and expensive hotel. The Habsburg family were experiencing severe financial difficulties during this time, despite the fact that Karl had not gone into exile without means: he had left Austria with eight railway wagons loaded with furniture and art objects from private Habsburg ownership.

There is also a mystery about the fate of the crown jewels, which Karl had taken into his possession before his departure and which are today presumed lost. In her memoirs, Zita always insisted that the jewels had been stolen while they were in exile. However, this is contradicted by statements made by the Swiss gem dealer Alphonse de Sondheimer, who claimed that he had broken up the jewels on Karl’s orders and sold the parts individually in order to raise funds unobtrusively. The part of Sondheimer’s memoirs dealing with this case reads like a detective novel.

The works of art and jewels that the imperial couple took into exile were sold in Switzerland and went towards financing the two attempts at a putsch in Hungary. The Western powers had originally intended the successor states of the Monarchy to pay the former emperor an annual sum of £20,000, but this was never implemented and meant that Karl’s family now found it difficult to finance their accustomed lifestyle.

The family was thus forced to find a cheaper alternative. The Villa Quinta de Monte was the summer residence of a local banking family who placed it at the disposal of the imperial couple. The estate lay in high up in the cooler mountain region of the otherwise subtropical island. Already severely weakened by Spanish influenza, Karl’s health deteriorated rapidly. On 1 April 1922, aged 35, Karl died surrounded by his family. A modest funeral took place quietly on 5 April 1922 in the church of Nossa Senhora do Monte in Funchal.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Um Krone und Reich. Die Tragödie des letzten Habsburgerkaisers, Wien 1968

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Zita. Die letzte Kaiserin, Wien 1993

Broucek, Peter: Karl I. (IV.). Der politische Weg des letzten Herrschers der Donaumonarchie, Wien 1997

Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. „Selig, die Frieden stiften ...“. Die Biographie, Wien 2004

Gottsmann, Andreas (Hrsg.): Karl I. (IV.), der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2007

Sondheimer, Alphonse de: Vitrine XIII. Geschichte und Schicksal der Österreichischen Kronjuwelen, Wien; Hamburg 1966

Unterreiner, Karin: Die Habsburger. Mythos & Wahrheit, Wien u. a. 2011

-

Chapters

- The Habsburgs in exile I: from Switzerland to Madeira

- Attempts to regain power

- Putsch attempts in Hungary

- Habsburgs in exile II: 1922-1945

- Zita – to the very last for ‘God, Emperor and Fatherland’

- Otto, the last ‘crown prince’

- Otto and Austrofascism

- The ‘Habsburg Crisis’

- The beatification of Emperor Karl I