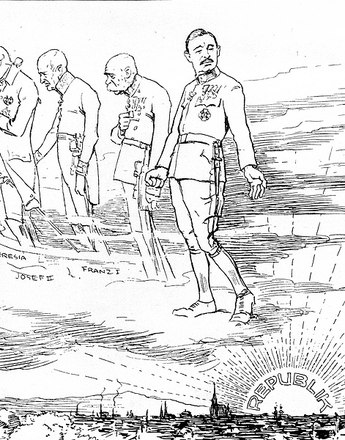

Otto Habsburg-Lorraine grew up as the figurehead of the legitimist movement. His use of the latter term was deliberately vague: as a politician he interpreted it as giving support to any lawful form of government. However, he must have been aware that in historical discourse legitimism is a synonym for dynastic monarchism.

In the 1950s he began to change his position, no longer agitating for the restoration of the Monarchy but instead advocating the ideal of a united Europe dedicated to Christian and democratic values.

However, this change of course was overshadowed by the beginning of the Habsburg Crisis in Austrian domestic politics, which led to a serious rift in the coalition government between the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the Socialist Party (SPÖ) under Federal Chancellor Alfons Gorbach (ÖVP).

How had this come about? In May 1961 Otto signed a document declaring that he no longer belonged to the House of Austria and thus renouncing all claims to the throne. The law now forbade Otto to call himself ‘Otto of Austria’; he was henceforth to be known as ‘Dr Otto Habsburg-Lorraine’.

However, the federal government continued to bar him from entering the country, citing unresolved property issues. Otto then turned to the Austrian Constitutional Court, which ruled in his favour in 1963. But the Austrian Socialist Party refused to give up its objections to his entering the country, thus sparking a government crisis.

Following the change of government in 1966, when the Austrian People’s Party had an absolute majority, Otto was allowed to enter the country. On 31 October 1966 he made a brief visit to Innsbruck, but left the country on the same day. This nevertheless led to massive protests from the left wing, accompanied by a strike by 250,000 workers on 2 November.

It was not until the reconciliation with the Social-Democratic Party under the government of Bruno Kreisky in 1970 that the situation resolved itself and the relationship of both political wings with the ‘last crown prince’ normalized.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Baier, Stephan; Demmerle, Eva: Otto von Habsburg, Die Biografie. 5. Aufl., Wien 2007

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Otto von Habsburg. Biografie, Graz-Wien-Köln, 2002

Riedl, Joachim: Ein letzter Hauch der Monarchie. Mit dem Tod von Otto Habsburg geht ein Kapitel österreichischer Geschichte endgültig zu Ende. In: Wochenzeitung Die Zeit, Nr. 28, 7. Juli 2011, Österreich-Ausgabe, S. 14.

-

Chapters

- The Habsburgs in exile I: from Switzerland to Madeira

- Attempts to regain power

- Putsch attempts in Hungary

- Habsburgs in exile II: 1922-1945

- Zita – to the very last for ‘God, Emperor and Fatherland’

- Otto, the last ‘crown prince’

- Otto and Austrofascism

- The ‘Habsburg Crisis’

- The beatification of Emperor Karl I