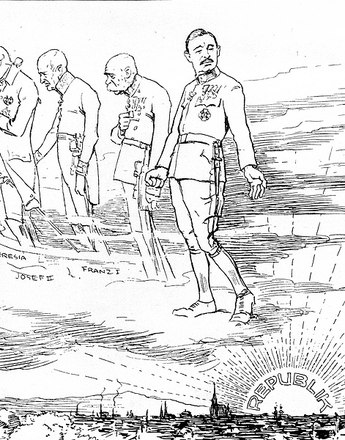

Emperor Karl’s refusal to abdicate was rooted in his conviction that he had been invested with imperial office by divine right and not by popular representation. However, in the several attempts he made to regain power he relied on more than mere divine providence, taking active steps and not shrinking from force of arms.

In the summer of 1920 Karl started preparing his return to Hungary. He was convinced that he would receive support from the Western powers, in particular France, which would regard his return as a sign of stabilization in the region.

However, reality proved to be different: in 1921 an alliance formed between the successor states of the Monarchy (Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia) which became known as the ‘Small Entente’. The main points of the alliance were adherence to the provisions of the Parisian peace treaties and the strict rejection of the restoration of Habsburg rule, if necessary through force of arms. Ignoring warnings from many sides and grossly misjudging the reality of the situation, Karl nevertheless went ahead with his attempt to regain power in Hungary.

The first attempted putsch was launched on 24 March 1921, when Karl entered Hungary in the utmost secrecy. Even his closest associates were not told of his plans. It was a hazardous journey: first, Karl crossed the border on foot from where he was living in the western Swiss town of Prangins to France, from where he took a train via Strasbourg to Vienna. As Karl did not possess a passport he entered Austria illegally under a false name.

On 25 March Karl arrived at the Viennese residence of Count Erdödy, a friend from his youth, who had reliable knowledge of the true conditions prevailing in Hungary and tried to dissuade Karl from proceeding with his plans. However, the latter set off for Hungary by car the next day, accompanied by Erdödy and again using a forged British passport. They took up quarters in the episcopal palace in the western Hungarian city of Szombathely. There the exiled king revealed himself to a group of monarchists led by Baron Anton Lehár (brother of the composer Franz Lehár).

Karl was staking his chances on the element of surprise. On 27 March he travelled alone to Budapest to see Horthy, who however refused to resign in Karl’s favour. Horthy justified his refusal by pointing to the risk of war: the Small Entente states would regard the return of the Habsburg monarch to the Hungarian throne as a cause for war.

Karl thus returned to Szombathely having achieved nothing. He remained there together with a small group of sympathizers. Following protests by the states of the Small Entente France officially denied supporting Karl, who initially remained in west Hungary, isolated and seriously ill. On 5 April 1921 he was expelled from the country and returned to Switzerland.

However, the former emperor continued to see himself as the rightful monarch, a position in which he was supported by the Vatican. Karl started another, precipitate attempt to return to power, as Horthy was successively neutralizing Karl’s supporters in Hungary. The second attempted putsch was far better organized: Karl was to be taken to Hungary by aeroplane, this time accompanied by his wife Zita. There he would meet up with loyal units in Sopron and with their backing take the train to Budapest.

On 20 October 1921 Karl and Zita flew from Zurich to Hungary. However, when they arrived, there was no sign of loyal troops, as the telegram in cipher with the command to mobilize had apparently failed to arrive ...

The journey to Budapest was thus postponed by 24 hours. This meant that the element of surprise was lost, and the enterprise could no longer be kept secret. In Sopron there were demonstrations of loyalty towards Karl. On the evening of 21 October the imperial couple set off for Budapest, accompanied by a hastily sworn-in ‘counter-government’ and 2,000 soldiers.

At first the journey became a sort of triumphal procession; whole units from the army swore an oath of allegiance to Karl. Alarmed by this news, Horthy began to take counter measures.

On 23 October the train came to a halt on the outskirts of Budapest. In the suburb of Kelenföld army units had taken up position. What happened next has never been clearly established, as extant eye witness accounts are very contradictory. Unsure of the loyalty of regular troops, Horthy ordered the deployment of a paramilitary unit of 300 students who were told that Czechoslovakian forces were marching on Budapest. There was a brief skirmish in which 19 people were killed. Conflicting orders led to chaos. Wanting to prevent further bloodshed, Karl eventually capitulated.

Karl and Zita were subsequently interned at the Benedictine monastery of Tihány on Lake Balaton. After Karl again refused to formally abdicate, the couple and their entourage were escorted out of the country by British army units.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Um Krone und Reich. Die Tragödie des letzten Habsburgerkaisers, Wien 1968

Broucek, Peter (Hrsg.): Anton Lehár. Erinnerungen. Gegenrevolution und Restaurationsversuche in Ungarn 1918–1921, Wien 1973

Broucek, Peter: Karl I. (IV.). Der politische Weg des letzten Herrschers der Donaumonarchie, Wien 1997

Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. „Selig, die Frieden stiften ...“. Die Biographie, Wien 2004

-

Chapters

- The Habsburgs in exile I: from Switzerland to Madeira

- Attempts to regain power

- Putsch attempts in Hungary

- Habsburgs in exile II: 1922-1945

- Zita – to the very last for ‘God, Emperor and Fatherland’

- Otto, the last ‘crown prince’

- Otto and Austrofascism

- The ‘Habsburg Crisis’

- The beatification of Emperor Karl I