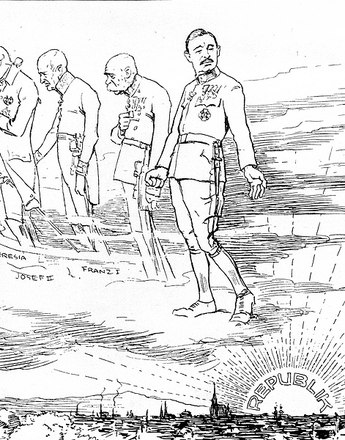

Karl’s ambitions to regain the power he had lost focused principally on Hungary. This provoked disquiet in the successor states of the Habsburg Monarchy.

The former emperor continued to regard himself as the rightful ruler. Karl clung to the erroneous belief that he still had great support among the ‘people’, and saw his fall from power as the result of an anti-Habsburg conspiracy. His first attempts to regain power started almost immediately, when he and his family and entourage were quartered at Schloss Eckartsau in the Marchfeld region of Lower Austria in the winter of 1918/19: Karl begged the British army officer E. L. Strutt to intervene with King George V, asking for a 5,000 to 10,000-man strong contingent of British soldiers to ‘restore order’. London did not even bother to reply to this unrealistic request.

The idea of a partial restoration of Habsburg power was in itself not wholly unrealistic given the turn of events in Hungary. A Bolshevist Soviet Republic under the leadership of Béla Kun had been proclaimed in March 1919. The spectre of Bolshevism made the Habsburg alternative seem the lesser (and more calculable) evil in the eyes of the West. However, for most of the successor states of the Habsburg Monarchy which had assembled in Paris for the peace conference, such as Czechoslovakia or Romania, this was inconceivable.

The reason why Karl’s efforts were concentrated specifically on Hungary lay in the development of the political situation there. After the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy, the country lapsed into chaos caused by extremist political parties. At first a council republic on the Soviet model was proclaimed in Budapest in March 1919 which under the leadership of Béla Kun (1886–1939) mutated into a regime of terror. Opposition forces gathered in Vienna and Szeged, where a right-wing government in exile formed propagating a return to the Monarchy. This group included the former Imperial and Royal Vice-Admiral Miklós Horthy (1868–1957), who was appointed commander-in-chief of the anti-Communist military forces. As a former aide-de-camp to Emperor Franz Joseph, he happened to have served as chauffeur to Karl and Zita at their wedding in 1911.

The Bolshevist republic was toppled by the Romanian army with support from the Entente powers on 3 August 1919. This set off counter-terror from the extreme right. Subsequently the Conservative faction in Hungary claimed that Karl’s renunciation of participation in the affairs of state was unlawful and propagated a return to the Monarchy. They were prepared to entertain the idea of a Habsburg other than Karl on the throne. One of the candidates suggested was Archduke Albrecht from the Teschen line, who had extensive estates in Hungary.

Another candidate was Archduke Josef from the Hungarian line of the dynasty. The latter had been appointed homo regius (governor) by Emperor Karl in October 1918. After the suppression of the Soviet republic in August 1919 Josef assumed the position of regent, in which capacity he appointed the government under Prime Minister István Friedrich and confirmed Horthy as head of the army. However, Archduke Josef resigned his office after just a short time.

In January 1920 a new constitution came into force in Hungary, declaring the country a monarchy without a king. In March 1920 Admiral Horthy was eventually appointed regent. Initially loyal to Karl, Horthy later endeavoured to uphold the status quo and prevented Karl’s return to the throne. Horthy established an authoritarian regime with chauvinist-nationalist tendencies. The mood in the country was characterized by an unimaginative conservatism, subsequently reinforced by the provisions of the Trianon peace treaty which entailed massive losses of territory for Hungary.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Brook-Shepherd, Gordon: Um Krone und Reich. Die Tragödie des letzten Habsburgerkaisers, Wien 1968

Broucek, Peter (Hrsg.): Anton Lehár. Erinnerungen. Gegenrevolution und Restaurationsversuche in Ungarn 1918–1921, Wien 1973

Broucek, Peter: Karl I. (IV.). Der politische Weg des letzten Herrschers der Donaumonarchie, Wien 1997

Demmerle, Eva: Kaiser Karl I. „Selig, die Frieden stiften ...“. Die Biographie, Wien 2004

Gottsmann, Andreas (Hrsg.): Karl I. (IV.), der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2007

-

Chapters

- The Habsburgs in exile I: from Switzerland to Madeira

- Attempts to regain power

- Putsch attempts in Hungary

- Habsburgs in exile II: 1922-1945

- Zita – to the very last for ‘God, Emperor and Fatherland’

- Otto, the last ‘crown prince’

- Otto and Austrofascism

- The ‘Habsburg Crisis’

- The beatification of Emperor Karl I