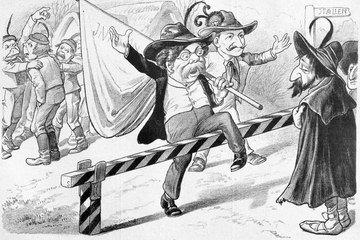

Élyen a Magyar – long live the Magyars! Hungarian Magyarization policy

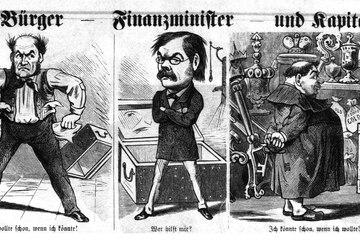

One of the fundamental differences between the two states in the Dual Monarchy after the Compromise of 1867 was that Hungary, unlike the Austrian half of the Empire, did not see itself as a multinational entity but rather as a Magyar nation state.