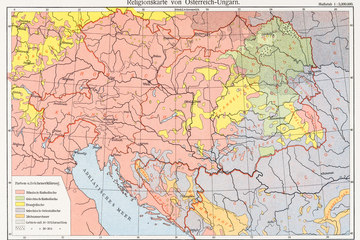

The Call for Autonomy

Coming next after the suppression of the 1848 Revolution was at first a political ice age. Nevertheless, the people’s demands could not be permanently ignored. National-liberal ideas had cast strong roots also in the Czech bourgeoisie, just emerging at the time.