The heroes in front of the camera

The military film propaganda focused on good news from the front. In addition, the mechanization and destructive efficiency were shown on film, along with the organization and discipline of the soldiers in action.

‘The film office pursues the military purpose of communicating the heroic deeds of the army on land and sea and of showing the life of the soldiers in the field and behind the lines.’

Der österreichische Komet, no. 429, 1918

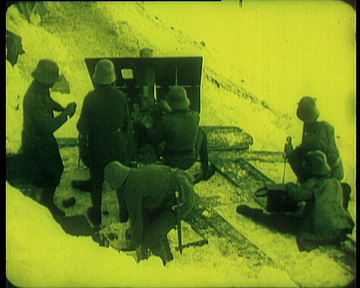

The exaggeratedly heroic depiction of the Austro-Hungarian soldiers, reports of successful actions and demonstrations of strength were the focuses of film propaganda. One particularly popular subject was fighting in the mountains. At altitudes of 2,000 to 3,000 metres there was little room for mobile warfare. On the Alpine front, where the fighting lasted until 1918, every promontory was bitterly contested. Twelve bloody battles took place on the Isonzo on the south-eastern front between Italy and Austria-Hungary. Days of preparatory artillery bombardment in narrow confines, difficult ammunition transports through the mountains, infantry attacks, bitter defence and close fighting for every mountain summit were the characteristic features of these battles and were faithfully shown in the film reports (A Heroic Battle in Snow and Ice, A 1917). Explosives were often used to destroy entire summits and the enemy lodged on them. But nature also claimed victims. In the winter of 1916/17 more soldiers died in avalanches than through enemy fire. The avalanches were often caused by artillery bombardment of enemy positions.

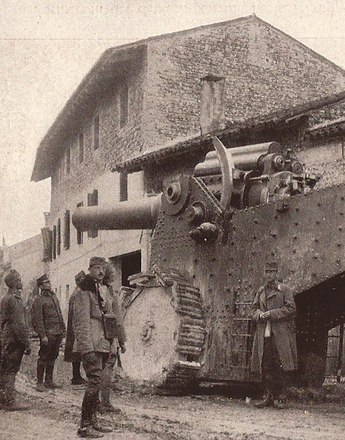

Propaganda productions like Mit Herz und Hand fürs Vaterland (A 1915) focused on modern warfare. Radio equipment, military aircraft and bombing raids were effectively demonstrated. The rapid mechanization of warfare and above all the marked improvement in destructive efficiency left their mark on both the static Western front in Europe and in the mobile warfare on the Eastern front. Within a few months, the firepower of industrialized mass killing had shaken the traditional values of the professional soldiers. Cavalry riders were mown down in the barrage of artillery and machine gun fire. Gas, tank and aerial attacks heralded a new form of warfare that put paid to any ideas of glory. Members of the old officer corps, who sought to lead their troops through demonstrations of personal bravery, suffered particularly high losses.

There were fewer films showing the more radical warfare in the Balkans and on the Eastern front, although photo series of executions of alleged or actual spies and collaborators were published particularly at the beginning of the war as a deterrent. The acts of violence against civilians were omitted. French, British and Dutch cartoonists, by contrasts, created a highly negative picture of the ‘German soldier’: the perfidious scientist who invented poison gas, the barbarian who destroyed churches and libraries, and the pitiless murderer who shot civilians.

Translation: Nick Somers

Kessel, Martina: Gelächter, Männlichkeit und soziale Ordnung. ‚Deutscher Humor’ und Krieg (1870–1918), in: Lutter, Christina/Szöllősi-Janze, Margit/Uhl, Heidemarie (Hrsg.): Kulturgeschichte. Fragestellungen, Konzepte, Annäherungen, Innsbruck/Wien/München 2004, 97-116

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Moser, Karin: Österreich Box 1: 1896–1918. Das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2010