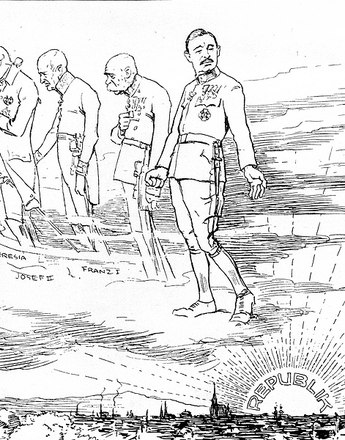

The idealized leader and monarch Emperor Karl in film – Christian, family-oriented, uniformed

After the death of Emperor Franz Joseph, the new young emperor and his wife became the focus of Austro-Hungarian film propaganda. The idea was to enhance their popularity and communicate calm, harmony and security amid all of the chaos.

After the death of the old emperor in the middle of the war, his successor Karl and his wife Zita became the symbols of hope of the Monarchy. On 30 December 1916 the new Emperor of Austria was crowned King of Hungary in Budapest (Coronation Celebration in Budapest, 27–30 December 1916, A 1916). The ceremony confirmed the basic pillars of the supranational state: the compromise between the Austrian half of the empire and the lands of the Crown of St Stephan. The crown appeared literally to be too big for its wearer, and when it slipped, some observers took it as a bad omen. Karl, who had been kept away from important government business and military decisions until then, was thought to be weak. For the time being, however, the celebration was seen as a way of weakening the independence of the Magyars, at least until a peace treaty was signed.

The film propaganda focused on the young emperor, who was shown as a loving father and Christian but also as supreme commander of the military. He was presented, particularly when the war was going well, as the highest representative of the Monarchy and army. Emperor Karl himself strengthened this impression when he appointed himself Supreme Warlord in 1916. Although decisions were normally made by chiefs of staff and in particular by the powerful German alliance partner, the responsibility as far as the public was concerned was with the dynasty and its head.

The longer the war lasted and the more the losses, shortages and hunger were felt by the population, the more the film propaganda attempted to portray normality amid the chaos. In the film Our Emperor (A 1917) Karl is presented as the ruler of all his subjects. He is given ovations wherever he goes in the empire. He is a military ideal, the ‘first Austro-Hungarian soldier’, who visited ‘his’ troops in the field, showing a popular and human face. The idea was to communicate that all was well with the world, as represented by the emperor and his wife – friendly, jovial and almost down-to-earth.

Translation: Nick Somers

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Moser, Karin: Österreich Box 1: 1896-1918. Das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2010

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013