Towards the end of the nineteenth century the Czechs availed of a fully developed spectrum of parties, with the parliamentary representatives of the Czechs in the Vienna Imperial Council assigned to different political camps.

The strongest and most influential camp accommodated the national parties of the bourgeoisie. Dominating this for a long time was the time-honoured National Party (Národní strana), also called Old Czechs (Staročeši). Founded in 1861, it represented the vanguard of the political emancipation movement among the nationally oriented Czechs. Later it developed into a party of notabilities of the economically satiated, established middle class, comparable with the German Liberals in the German parties. Analogous to the development of German like-minded politicians, the Old Czechs were superseded by the more radical Liberal National Party (Národní strana svobodomyslná), better known as Young Czechs (Mladočeši), who finally split from the old mother party in 1874. The Young Czechs pursued a pronounced national line and formed the Czech counterpart to the German nationalist party. Both parties shared an antipathy to clericalism, which could escalate to militant anti-Catholicism, and the emphasis on nationalist ideas. Despite comparable positions and a similar radicalness in their practical action, they were hostile to each through being separated by national barriers.

Likewise belonging to the middle-class parties were minor parties like the Czech Progress Party (Česká strana pokroková), whose most honorific member was the later first Czechoslovakian President Tomáš G. Masaryk, and the Radical Constitutional Law Party (Strana statoprávní radikalně). Both parties pursued policies influenced strongly by democratic ideals, their main long-term objective being the establishment of an independent Czech state.

The left camp was conspicuously weakened by the increasing nationalisation of politics. Contrary to the ideal of supranational solidarity among the working class, a split occurred here along ethnic borders. The Czechoslovakian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Českoslovanská sociálně demokratická strana dělnická, founded in 1878) had a strong backing from the nationally oriented Czech industrial workers. In 1911 the central wing split off; it pursued a more internationally oriented approach and based its agenda on Pan-Austrian Social Democracy.

The National-Social Party (Strana národně sociální, founded in 1897/1899) was another splinter party from the Social Democrats and linked a social agenda to a strongly national, in part nationalistic-chauvenistic perspective. This party found support in the national circles of the working class and petty bourgeoisie.

The national Catholic milieu was also vehemently split on account of the strongly liberal-to-anti-Catholic tendencies in the process of the Czech nation’s evolution. The Christian camp established itself as a political force only in the more strongly Catholic Moravia, where the Christian Social Party (Křesťansko-sociální strana, founded in 1896), which unambiguously professed allegiance to the Czech national programme, attained a similar significance to its Christian-Social counterpart in the German-speaking parts of the empire.

In the rural areas the Czech Agrarian Party (Česká strana agrární; created around 1900 as a coalition of several minor parties), which had developed out of the national liberal parties, continued to play an important political role.

While the liberals increasingly concentrated on the urban clientele of the growing middle class, the Agrarians acted as the mouthpiece of the farmers. Typical of the professional alignment of this party was the strong economical orientation of their aims, such as a reinforcement of the cooperative movement, but without forgetting Czech-national demands.

In conclusion, there was a relic of the time before the genesis of modern mass parties: the Party of Conservative Land Owning Magnates (Strana konzervativního velkostatku). After the introduction of the general franchise in 1911 this was represented only in the Upper House thanks to inherited seats for (mainly aristocratic) land magnates. It was a reservoir for liberal representatives of the aristocracy who professed allegiance to the demands of the Bohemian Constitutional Law (thus to an autonomy of Bohemian countries within the Habsburg Monarchy), but which nevertheless remained ambivalent with regard to national issues. They saw themselves as “Bohemian” and not Czech in the modern national sense.

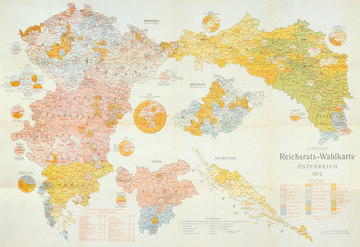

A total of 108 Czech members (out of 516 seats in all) from mainly Czech-speaking constituencies was represented in the Vienna Parliament after the Imperial Council elections of 1911 – the last before the outbreak of the First World War. After painful losses for the radical-nationalistic Young Czechs, now making up a great deal of ground were the Agrarian Party, the Social Democrats and the National Social Party.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Kořalka, Jiří/Crampton, Richard J.: Die Tschechen, in: Wandruszka, Adam/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band III: Die Völker des Reiches, Wien 1980, Teilband 1, 489–521

Kořalka, Jiří: Tschechen im Habsburgerreich und in Europa 1815 bis 1914. Sozialgeschichtliche Zusammenhänge der neuzeitlichen Nationsbildung und der Nationalitätenfrage in den böhmischen Ländern (Schriftenreihe des Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Instituts 18), Wien 1991

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Velek, Luboš: Die tschechischen bürgerlichen Parteien im Weltkrieg 1914–1918, in: Der Erste Weltkrieg und der Vielvölkerstaat (Acta Austro-Polonica, IV), Wien 2012, S. 165–178

-

Chapters

- The Czechs in the Habsburg Monarchy

- How Czechs evolved from Bohemians

- The Revivalists of the Nation

- Separate Ways: The Effects of the 1848 Revolution in Bohemia

- The Vectors of Czech National Identity

- The Call for Autonomy

- Hardening of the Fronts: The Czech Demand for the Bohemian Compromise

- Attempts at Solutions and Escalation: Language Conflict and Badeni Crisis

- The Czechs’ Spectrum of Parties

- The Lack of Alternatives: the Attitude of the Czechs towards the Habsburg Monarchy at the Outbreak of the War