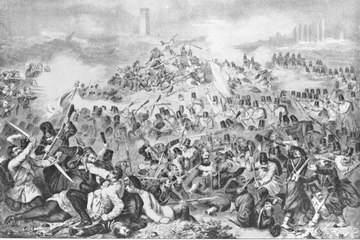

The "right of the peoples to self-determination" – the patent solution to ethnic conflicts?

For the national movements of the peoples of the Habsburg Monarchy, the final objective of national development was seen as being complete cultural and political autonomy or even their own national state. The slogan of the "right of the peoples to self-determination" was on everyone's lips.