The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

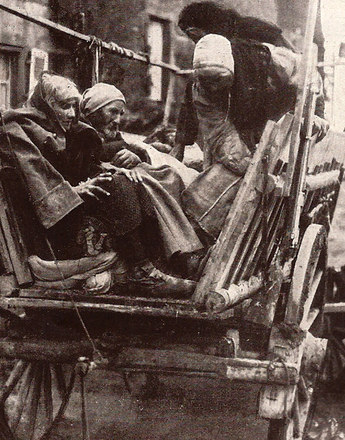

During the German invasion of Belgium and France, repeated assaults took place on the population there. This triggered a mass exodus. Over 4 million civilians sought protection from the German army in the hinterlands. The population’s fears in this regard were not unfounded.

The German invasion of the neutral states of Luxembourg and Belgium already signified a breach of international law. That the German Empire was aware of this breach of law is shown by the speech held in the German Imperial Parliament by chancellor Bethmann Hollweg of August 4, 1914: "Gentlemen, we are now in a position of self-defence, and this emergency knows no law! Our troops have occupied Luxembourg, perhaps already entered Belgian territory. Gentlemen, that contradicts the dictates of international law […]. The injustice – I speak openly – the injustice that we commit in so doing, we shall seek to make good again as soon as our military goal is reached." This breach of international law was justified with the reference to a ‘necessity of war’. The Allies rejected the appeal to a ‘necessity of war’ because it was suited for the purpose of turning upside down any kind of law of war.

The German invasion led to a mass exodus of Belgian and French civilians, fearful of landing in between the military fronts, and of the aggression of German troops. Their fear was in no sense unjustified. In the early months of the war already some 6,500 Belgian and French civilians fell victim to German soldiers. This number refers only to those persons killed deliberately and does not include all those who had to perish in the course of regular combat activities. Hundreds of civilians were also taken hostage in order to protect German troops from attacks, functioning as human shields. Besides, the invasion caused enormous material damage due to arbitrary acts of arson and shelling.

Yet how could it come to mass executions like in Dinant (August 23, 1914) or to the destruction of entire cities like in Löwen (August 25 to 28, 1914)? On the one hand, due to the mental and physical overstretching of German soldiers who could carry out the operational Schlieffen Plan only with great difficulty. The intended rapid march through the country simply could not be managed, not least of all due to the unexpected and vigorous defensive war waged by the Belgian army. On the German side, one had not anticipated the intense resistance on the part of this small country. Historian Alan Kramer believes – with reference to the notes made by leading German officers that "[...] Belgium [was] denied any right to self-defence as an inferior nation and its military resistance criminalised [...]. Belgium as a nation was denied the right to defend its neutrality; in line with this, Belgian and French civilians were stripped of the right to resist. This posed a kind of criminalisation, which prepared the way for civilians not to be treated according to the rules of international law."

On the German side, recriminations were made against the Belgian resistance for resorting to strategies that ran counter to international law. The Belgians waged a so-called franctireur war, it was claimed, in which civilians sneakily shot at Germans from behind their backs. What was seen as particularly treacherous was that their combatant status was not visible. It was said that as guerrillas they not only wore no uniform, they also hid their weapons under their civilian clothing. They were thus unrecognisable as the foe. In this way civilians were all tarred with the brush of being guerrillas, which, it was assumed, was supported and organised by the Catholic Church. This recrimination was, however, flimsy and did not correspond to reality. Almost all of the so-called franctireur attacks were supported either by regular Belgian troops or resulted from the chaotic conditions within the German army. The constant excessive demands placed upon the soldiers, the general nervousness, immoderate consumption of alcohol and confusing rearguard actions resulted in scenes of chaotic shooting, in which the German troops unintentionally found themselves firing against each other – thus suspecting the so-called franctireurs.

While there may have been isolated cases of armed resistance on the part of the civilian population, this was the exception and was in no way organised from ‘above’. Regardless of this, the spectre of the franctireur lurking behind every bush became a firm feature of the German soldier’s imagination, explaining why later authors spoke of regular ‘franctireur psychoses’.

Together with the excessive mental and physical demands and the military reverses suffered, this led to devastating outbreaks of violence against the civilian population. Thus one soldier wrote in a letter dated September 10, 1914: "In Belgium the franctireurs caused us […] a lot of trouble. […] Yet the Belgians had to pay dearly for this. In villages where we came under fire, we razed the […] village to the ground. In one village, we shot 35 men and also some women, including 2 priests. […] They all lay piled up. The villagers were herded together and had to watch the events, then were released."

Kramer, Alan: Kriegsrecht und Kriegsverbrechen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, 3. Auflage, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2009, 281-292

Kramer, Alan: „Greueltaten“. Zum Problem der deutschen Kriegsverbrechen in Belgien und Frankreich 1914, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich,Gerd/Renz, Irene (Hrsg.): „Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch“. Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkrieges, Essen 1993, 85-114

Überegger, Oswald: „Verbrannte Erde“ und „baumelnde Gehenkte“. Zur europäischen Dimension militärischer Normübertretungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 241-278

Quotes:

„Gentlemen, we are now...": Bethmann Hollweg, Theobald, quoted from: Kramer, Alan: Kriegsrecht und Kriegsverbrechen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, 3. Auflage, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2009, 282 (Translation)

"[...] Belgium [was] denied any right...": Kramer, Alan: „Greueltaten“. Zum Problem der deutschen Kriegsverbrechen in Belgien und Frankreich 1914, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich,Gerd/Renz, Irene (Hrsg.): „Keiner fühlt sich hier mehr als Mensch“. Erlebnis und Wirkung des Ersten Weltkrieges, Essen 1993, 91 (Translation)

"In Belgium the franctireurs...", Brauch, Arthur, quoted from: ibid. 101 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

- The First World War and the law on war in effect

- The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

- Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

- The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

- War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

- Prohibited war material: Dum-dum shells and deployment of gas

- The Leipzig Trials (1921-1927). Between national disgrace and juridical farce