International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

When is it legally acceptable to wage war and what is just in a war? These questions appear holier-than-thou in view of the enormous suffering that war brings with it. And yet, wars never take place in a complete legal vacuum. Rather the opposite is the case.

Under what circumstances is it justified to wage war? This question was already posed in ancient Rome. Thus Cicero (106 - 43 B.C.) points out that the right to wage war is subordinate to certain conditions. A war is only justified when it happens for reasons of defence or to exact revenge. Moreover, ancient notions of law demanded that a war may not begin as a surprise, but must be declared beforehand in a solemn proclamation. In the Middle Ages in Europe war also required a certain reason, whereby according to Christian understanding it was only justified when it represented a reaction to an injustice previously suffered. According to Thomas Acquinas (1225 - 1274), a just intention and the authority of the prince or king had also to be present.

Building on this tradition, the Dutchman Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) developed his treatise ‘De jure belli ac pacis libri tres’ (On the Law of War and Peace: Three books). For Grotius, considered today the founder of classic international law, a war was only legitimate when it served the purposes of defence, the recovery of property or as a punishment. What was not seen as legitimate was merely striving to extend territory or suppress the enemy nation.

At the same time as Grotius’ reflections on a just war, the process of forming states was gathering momentum. The international law expert Udo Fink believes as follows: "With the emergence of the primacy of state sovereignty, the notion then took hold at the beginning of the 17th century […] that it is the right of every single sovereign state to wage war for any given reason." Admittedly, the attempt was made at the Peace of Westphalia (1648) to restrict the complete arbitrariness of war by means of internationally binding treaties, yet the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) was the first to regard offensive warfare as illegitimate, a consequence of the First World War.

Humanitarian international law was a further feature of the law of war. In contrast with the ius ad bellum, i.e. the right to wage war, the ius in bellum regulates the conduct of war itself. Aspects covered here include the treatment of prisoners of war, the wounded and civilians as well as the deployment of certain means of making war and tactics employed.

While the disputes in this area reach back to ancient Rome too, this aspect likewise only acquired greater significance in the 19th century. There were two changes crucial in this: the spreading of humanistic ideals and the introduction of universal conscription. Where once a limited number of mercenaries or soldiers had gone to war against each other, the new wars between peoples and massed forces affected ever broader segments of society.

Moreover, the effects of ‘modern’ wars were plainly shown by the mass press to an ever wider and increasingly critical public. Here in particular, the Crimean War (1853-1856) was the first to achieve broad media attention. The British nurse Florence Nightingale made known the soldiers’ sufferings to the public at large.

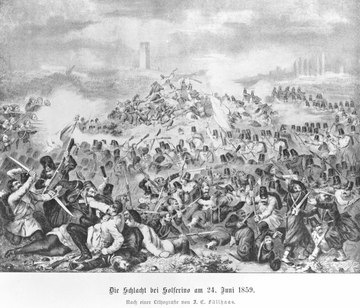

The Swiss businessman Henry Dunant experienced the situation of wounded soldiers at the Battle of Solferino (1859) and made a key contribution to the founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross (1863) and the Geneva Red Cross Convention (1864).

From the mid-19th century, attempts were made, moreover, to codify norms of the law of war. Here it was the Lieber Code of 1863, which as a consequence of the American Civil War (1861-1865) reflected the law of war that was in force at the time. A humanitarian law of war international in character first arose around the end of the 19th century. This included the Hague Conventions that arose from the peaces conferences in The Hague from 1899 and 1907 as well as the Geneva Convention of 1906, the first forerunner of which was the first Red Cross Convention of 1864. While the Hague Convention in particular encompassed the laws within the waging of war, the Geneva Convention focused on humanitarian aspects for the protection of combatants and the civilian population.

Fink, Udo: Der Krieg und seine Regeln, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 39-56

Segesser, Daniel Marc: „Moralische Sanktionen reichen nicht aus!“ Die Bemühungen um eine strafrechtliche Ahndung von Kriegsverbrechen auf nationaler und internationaler Ebene, in: ibid., 57-74

Quotes:

"With the emergence of...": Fink, Udo: Der Krieg und seine Regeln, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 40 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

- The First World War and the law on war in effect

- The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

- Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

- The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

- War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

- Prohibited war material: Dum-dum shells and deployment of gas

- The Leipzig Trials (1921-1927). Between national disgrace and juridical farce