The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

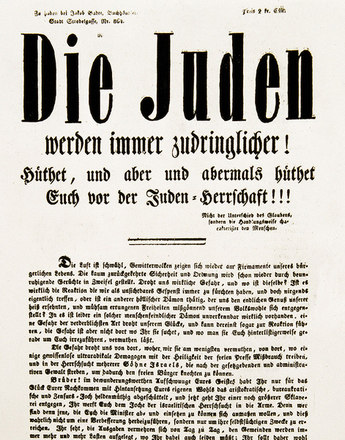

Driven by resentment and suspicions of spying, the Habsburg army persecuted parts of its own population as the ‘enemy within’. Yet many thousands of civilians fell victim to the soldiers’ acts of atrocity during the military invasion, too. Besides the war crimes of the marauding troops, the Habsburg military courts also distinguished themselves with an inglorious ‘efficiency’.

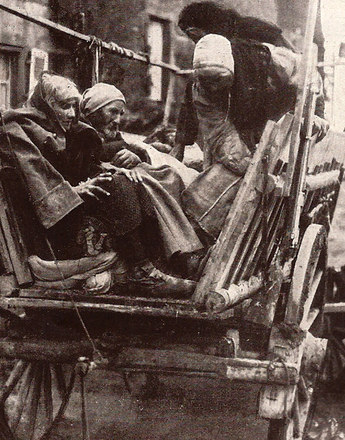

There was intense resentment on the part of the Austro-Hungarian army towards the ethnical-religious minorities within their own state, as well as towards civilians in the occupied territories. This led to excessive distrust of certain segments of the population, who were under general suspicion of untrustworthiness, espionage and collaboration with the enemy. The acts of violence committed by the Habsburg army were aimed in particular at the Jewish, Polish and Ruthenian population in the Bukovina, Galicia and the occupied Russian regions, as well as against the Serbian, Montenegrin and Bosnian population in the conquered areas in the Balkans. According to historian Anton Holzer, the excesses were "[...] arranged and planned at the highest level. They included hostage-taking and hostage-shootings, massed deportation, incarceration and forced labour – and [...] mass executions. The violent politics of the military was accompanied by further violent excesses that were in part tolerated, in part left unpunished: rape, looting, arbitrary killings and the destruction of houses."

An Austrian soldier who invaded the Serbian city of Šabac in August 1914 describes the arrangement as follows: "We received the order, and this was read out to us loudly, to kill everyone and to burn down everything that crossed our path in the course of this campaign, and to destroy all that was Serbian." During the Massacre of Šabac looting and arson took place over several days, the population was interned, humiliated, maltreated, raped and arbitrarily murdered. In the course of these atrocities – costing some 200 civilians their lives – there also occurred a mass shooting: on August 17, 1914 the villagers were herded in to the church square, around 80 of them ordered to be shot dead and buried in a mass grave.

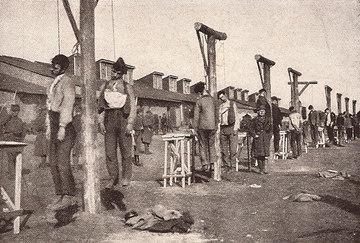

Besides the soldiers, the Austrian-Hungarian military judiciary also played an inglorious role in war crimes against the civilian population. The Habsburg military courts decreed the death sentence on a mass scale. Even though the scale of executions is hard to reconstruct today quantitatively, it can be assumed that the number of victims killed runs into the thousands. According to various sources, between 11,400 and 36,000 civilians were condemned to the gallows in the early months of the war already. Additional hangmen had to be recruited and trained by the authorities as early as 1914 in order to carry out the numerous death penalties. Oftentimes no particular event was needed to set in motion the martial law machine: a thoughtless comment, a flimsy suspicion or a hint dropped by an informer was mostly more than enough to ensure an innocent civilian swung from the gallows. Moreover, there were increasingly ‘wild’ executions occurring outside of the military tribunals. In such cases, sentence was passed by the commanding officer alone.

The military jurisdiction eliminated its victims preferably by means of the gallows on the main squares of villages and towns, forcing the population to attend the executions. The lifeless bodies were then left to hang by the noose for several days so as to clearly show the treatment meted out to ‘spies’ and ‘traitors’ by the Austro-Hungarian army.

Holzer, Anton: Das Lächeln der Henker. Der unbekannte Krieg gegen die Zivilbevölkerung 1914-1918, Darmstadt 2008

Überegger, Oswald: „Verbrannte Erde“ und „baumelnde Gehenkte“. Zur europäischen Dimension militärischer Normübertretungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 241-278

Quotes:

"[...] arranged and planned...": Holzer, Anton: Das Lächeln der Henker. Der unbekannte Krieg gegen die Zivilbevölkerung 1914-1918, Darmstadt 2008, 12 (Translation)

"We received the order...": Soldat (Anonym) des 26. Regt., quoted from: ibid., 118 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

- The First World War and the law on war in effect

- The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

- Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

- The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

- War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

- Prohibited war material: Dum-dum shells and deployment of gas

- The Leipzig Trials (1921-1927). Between national disgrace and juridical farce