War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

In the course of the First World War between 7 and 8.5 million soldiers are estimated to have been held prisoner. The prisoners of war, according to the Hague Land War Convention, were under special protection. In general they possessed the right to be treated with ‘humanity’. Yet despite a series of coded prohibitions and regulations, hundreds of thousands of them perished. The chances of surviving captivity varied considerably in the various countries concerned.

In 1894 the German international law expert Heinrich Triepel formulated the principle that prisoners of war are to be considered political rather than criminal prisoners. The rights and duties arising from this status were first laid down in written form in the Hague Conferences (1899/1907) through codification of the common law in force up to then. In principle, prisoners of war were not allowed to be killed, nor to be maltreated. They "[...] should be treated with humanity" and were to be protected from any acts of vengeance. In order to be able to guarantee this, they were subordinate to the enemy government concerned, not to the military unit which had captured them (art. 4). They were "[...] to be treated on the same footing as the government troops who had captured them with regard to food, upkeep and clothing" (art. 7). While they could be used by the state as workers – with the exception of officers – such jobs "[...] may not be excessive and may not be related to the activities of the war" (art. 6).

The treatment of prisoners took very different shape in the countries waging war and the fronts concerned. Prisoners of war in the German Empire could reckon with conditions that were to some extent ‘humane’. While there were also widespread cases of moderate maltreatment here too, nonetheless, drastic use of force remained the exception to the rule. Yet thousands of soldiers died here as well. Hence some 70,000 Russian, 18,000 French and 5,500 British prisoners of war lost their lives. The causes of death, according to the Irish historian Alan Kramer, were "[...] primarily the result of organisational inadequacies, shortages of food and incompetence, yet not of brutality."

In comparison, the likelihood of surviving in a Russian or a Habsburg prisoner of war camp was considerably lower. While in the German Empire around 5 percent of prisoners of war perished, the same figure was around 20 percent in the Danube Monarchy, and in Russia even more than 26 percent.

Key to the mortality rate in the Habsburg Monarchy were the shortage of food provisions on the one hand – something the German Empire had to struggle with too, after all – and the neglect on the part of the Habsburg administration, the use of violence as well as hard and dangerous forced labour on the other. One contemporary described the situation of Russian prisoners of war as follows: "Half-starved existences without any protection of their interests, the heaviest physical labour, inhuman physical and mental distress – that wears out the prisoners’ powers, resulting in their death. To force the prisoners to work, use is made of rods, chains, being driven by dogs, being hung up, being crucified, cold water, reductions in the already so inadequate food rations, clubs and bayonets – to the point of being shot dead."

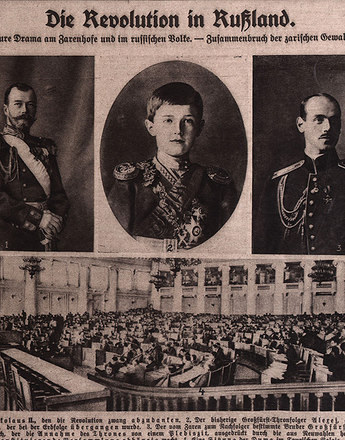

The situation of soldiers interned in Russia turned out to be even more fatal. Here too, it was the shortages in food – exacerbated in particular by the revolution of 1917 – and the ‘maltreatment at the hands of guards, medical neglect and excessive forced labour under often extreme climactic conditions that took the lives of thousands of internees. For example, infamy was achieved by the construction of the Murman Railway, of strategic importance militarily, about which the Hungarian historian Antal Józsa writes as follows: "To the end of 1916, when the railway transport began [...], of the 80,000 prisoners of war who were employed at various periods on this construction site, some 25,000 to 28,000 perished at the work location and in hospitals as a result of health-damaging conditions and maltreatment at the hands of the railway company’s supervisors."

Hankel, Gerd: Die Leipziger Prozesse. Deutsche Kriegsverbrechen und ihre strafrechtliche Verfolgung nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 2003

Józsa, Antal: Háború, Hadifogság, Forradalom. Magyar Internacionalista Hadifoglyok az 1917-es Oroszországi Forradalmakban, Budapest 1970

Kramer, Alan: Kriegsrecht und Kriegsverbrechen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2009, 281-292

Sergeev, Evgenij: Kriegsgefangenschaft aus russischer Sicht. Russische Kriegsgefangene in Deutschland und im Habsburger Reich (1914-1918), in: Forum für osteuropäische Ideen- und Zeitgeschichte, 1 (1997), 113-134

Wurzer, Georg: Die Kriegsgefangenen der Mittelmächte in Rußland im Ersten Weltkrieg, Diss. Universität Tübingen 2000

Quotes:

"[...] should be treated with humanity...": Haager Landkriegsordnung, Abkommen betreffend die Gesetze und Gebräuche des Landkriegs, 18. Oktober 1907, RGBl. 1910, 134 (Translation)

"[...] to be treated on the same footing...": ibid., 135 (Translation)

"[...] may not be excessive...": ibid., 134 (Translation)

"[...] primarily the result of organisational ...": Kramer, Alan: Kriegsrecht und Kriegsverbrechen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumreich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2009, 287 (Translation)

"Half-starved existences...": Sergeev, Evgenij, quoted from: Wurzer, Georg: Die Kriegsgefangenen der Mittelmächte in Rußland im Ersten Weltkrieg, Diss. Universität Tübingen 2000, 488 (Translation)

"To the end of 1916...": Józsa, Antal, quoted from: ibid., 341 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

- The First World War and the law on war in effect

- The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

- Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

- The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

- War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

- Prohibited war material: Dum-dum shells and deployment of gas

- The Leipzig Trials (1921-1927). Between national disgrace and juridical farce