Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

During the First World War international attention and propagandistic indignation – on account of the invasion of Belgium that violated international law alone – was directed against the German war crimes on the Western front. This resulted in crimes in other theatres of war receiving mostly little attention, although the scale on the Eastern and Southern fronts significantly exceeded that of the Western front.

The war in the East had a completely different character to that in the West. While the Western front soon changed to the deadlock of trench warfare following the German invasion of Belgium and North France, the front lines in the East remained broadly dynamic. The continuous offensive and rearguard actions resulted in the front sections being characterised by permanent mobilisation, and some areas were occupied many times and then evacuated again. In particular Galicia and Bukovina, East Prussia and Russian-Poland were affected as well as the Baltic.

The regular potential for danger represented by the ongoing mobilisation and continuous armed conflicts already proved devastating for the civilian population. Added to this was the fact that all sides waging war in the East pursued the burned earth strategy in rearguard actions, i.e. the systematic destruction of infrastructure. Yet this tactic was illegal according to the Hague Land War Convention (HLWC), article 23(g), as this prohibited the ‘destruction or removal of enemy property’ not required for war. The devastations were enormous, however, and extended beyond what was necessary for war. Thus, for example, an Austrian commission report shows that just in the north-eastern territories of the Habsburg Empire around 177,000 buildings were destroyed up to winter 1916. Particularly affected were those areas in which the occupiers often changed. This included the land strip between Cracow and Rzeszów, for instance, which had been taken and then evacuated nine times by the end of the end of the war.

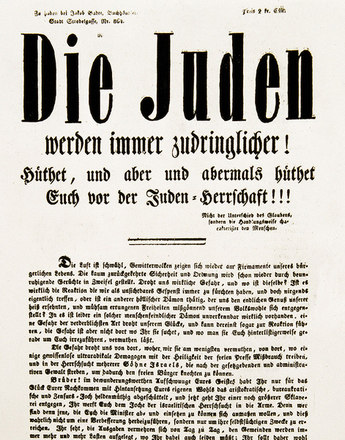

A further striking difference to the Western front lay in the ethnic-religious heterogeneity of the population living in the East. Since the beginning of the war an exaggerated military mistrust towards the domestic minorities in the population had been coupled with religious, ethno-political and in part social-Darwinist grievances. On the part of the military authorities these minorities, which in many cases lived near the outer borders and thus the theatres of war of the Empire, were considered unreliable ‘enemies within’. Already soon after the war began, they were thus the subject of wholesale suspicion by their own state of spying, treason and collaboration with the enemy. These allegations led to a sinister expansion of the combat zone. The minority population in these areas had not only cause to fear the atrocities of foreign invaders and occupiers, but also their own army.

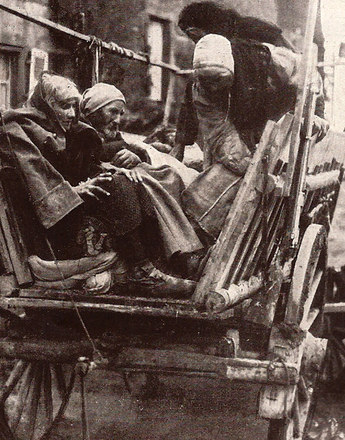

In the Russian Empire the Jewish and German minorities in particular were suspected of ‘unreliability’. As they were accused across the board of collaborating with the enemy, the Russian army began to remove them from the sensitive areas at the front and in the rear zones in the early months of the war already. These expulsions, initially unsystematic, soon took on the character of mass deportations. In total the Russian army forcibly removed and drove off around one million Jews as well as tens of thousands of Germans from the border regions. These deportations many times went hand in hand with pogroms, massacres and looting. In December 1914 the army chaplain Arthur Levy wrote as follows concerning the lot of Jews in Russia: "My heart contracts when I see and hear what dreadful atrocities have been carried out here in Poland against Jews by Russians in the course of this war, and still are daily. The pogroms of earlier times are as nothing against the relentless destruction of Jewish houses and Jewish life, which rolls with the Russian army throughout Poland, with it forwards, with it backwards, accompanying it like a menacing shadow. In more than 215 places pogroms have been carried out up to now, and there is no end in sight to this terror!"

At least as ruthless was the way that Russians proceeded against the civilian population in the areas occupied by them. After the Russian army occupied Bukovina and Galicia in the summer of 1914, severe attacks occurred here against those Jews who had not yet fled. Here too there was anti-Semitic resentment in connection with the sweeping suspicion of espionage and collaboration with the enemy, which led to mass-scale executions, arbitrary acts of violence, rape, destruction and looting. This is how the contemporary Leon Weinrebe writes of the Russian incursion on the city of Dębica (now in Poland): "Around 8 o’clock in the morning the Cossacks arrived in Dembica. The Jews who had already survived the initial agonies of looting of the usual ‘good’ troops were gathered in the synagogues with their wives and children […]. The Cossacks plunged into the Jewish houses with their horses and weapons – and what was not screwed down, was smashed and then flung onto the open street. Like wild beasts they threw themselves on the defenceless women […] and raped them. Those who defended themselves were stabbed and trampled to death. Spirited women plunged through windows, badly injuring themselves, but these too were not left alone by the monsters, many died on the synagogue square from the bloody beating of the nagyka in agonies of pain. […] The synagogue street was then set alight, and after a short while a whole row of houses stood ablaze." The extent of the attacks intensified in particular with the Russian retreat from April to October 1915. Besides the massive increase in pogroms and massacres, this meant that "[...] the Jewish population […] was literally driven to the front hunt-like, and forced against the Austrian positions."

Überegger, Oswald: „Verbrannte Erde“ und „baumelnde Gehenkte“. Zur europäischen Dimension militärischer Normübertretungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 241-278

Quotes:

"My heart contracts when...": Levy, Arthur: Zur Lage der Juden in Rußland, insbesondere in Russisch-Polen. Offener Brief an „The American Hebrew" in New York. Von Rabbiner Dr. Arthur Levy, z. Z. in Lodz als Feldprediger bei der deutschen Armee im Osten, Lodz, 24. Dezember 1914; in: Jüdisches Archiv, Mitteilungen des Komitees „Jüdische Kriegsarchiv“ (Nr. 1), Wien 1915, 19 (Translation)

"Around 8 o’clock...": Weinrebe, Leon: Die Kosaken in Dembica. Nach Bericht von Leon Weinrebe an das „Frankfurter Israelitische Familienblatt“; in: ibid., 10 (Translation)

"[...] the Jewish population...": Überegger, Oswald: „Verbrannte Erde“ und „baumelnde Gehenkte“. Zur europäischen Dimension militärischer Normübertretungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Neitzel, Sönke/Hohrath, Daniel (Hrsg.): Kriegsgreuel. Die Entgrenzung der Gewalt in kriegerischen Konflikten vom Mittelalter bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Paderborn/München/Wien/et al. 2008, 266 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- International laws of war. Genesis of a juridification

- The First World War and the law on war in effect

- The Western front. Guerilla poses and war waged on the civilian population

- Russia’s ‘enemies within’. Jewish and German minorities on the Eastern Front.

- The war crimes of the Habsburg army. Between soldateska and court martial.

- War imprisonment. The right "to be treated with humanity"

- Prohibited war material: Dum-dum shells and deployment of gas

- The Leipzig Trials (1921-1927). Between national disgrace and juridical farce