Dreamers Who Turn into Heroes

Austrian literature on the First World War has strands which are in favour of war and heroics, but it also makes repeated references to the culture of the lower orders with its enjoyment of the pleasures of life, the theatrical playfulness and gentleness of the Austrians and the artistic mentality of the dreamers from – to quote the writer Anton Wildgans – ‘the people of dancers and of fiddlers’, who become heroes ‘when it is necessary’.

'The great day had arrived, I too had really been wishing for it to come. Attack! Who would have imagined that this magic word of chivalry would abruptly transform my fine regiment of dragoons into a bloody mass, man and horse alike, in which more and more horses dashed, as if whipped on by ghosts and frightened, only to collapse together with their riders in the gunfire. It all happened much too quickly for one to be able to think of heroic deeds. Just don’t be crushed underfoot like a worm! The hotspurs among us fell into the trap into which they had been lured. I had seen the Russian machine guns clearly before I felt a dull thud against my temples.'

Kokoschka, Oskar: Schriften 1907-1955, hg. von Klaus Maria Wingler, München 1956, 69-76

In Richard Schaukal’s poems from the collection Eherne Sonette (Brazen Sonnets) 1914 (1914) the men with their weapons to hand want to ‘pull together’ out of ‘joy at the dance of the weapons’ in order to follow the call of the emperor and to gain victory: ‘They all feel it: pull together,/ is the command for the empire. It is not the drill which forces us. Every clenched fist says: Swell up, sinew of my heart, to bring us victory.’ In spite of the aggressive tenor of this poetic mobilization, which makes even the youngest boys ‘united as one squad’ start to play with weapons, it is made clear that Austria’s men are not driven by drill and compulsion but bow to the emperor’s will out of conviction. The prospect of the fine uniforms, manly adventures and heroic cavalry attacks was an attractive one for many men. In his well-known memoirs The World of Yesterday (1942) Stefan Zweig points out the origin of this romantic legend of war: ‘A rapid excursion into the romantic, a wild, manly adventure – that is how the war of 1914 was painted in the imagination of the simple man, and the young people were honestly afraid that they might miss this most wonderful and exciting experience of their lives; … .’

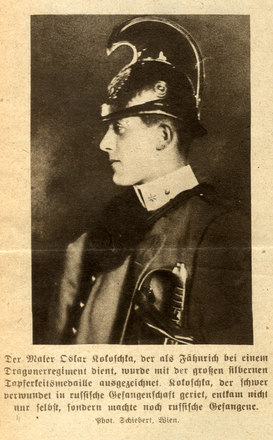

Many Austrian writers were also dazzled by the romantic visions of war and went voluntarily to war. The proud cavalry officer Oskar Kokoschka hoped, as he admitted in his memoirs Mein Leben (My Life) (1971) that he would ‘heroically overrun the enemy’ in a cheerful and adventurous cavalry war ‘with trumpets and waving flags’. It was not only in his case that the ‘marvellous and exciting’ elements of this vision of war were transformed into virtually unimaginable challenges to a man’s physical and mental powers, infernal conditions at the front, experiences of suffering and pain that had little to do with adventure, and the danger of ‘sinking down to the slaughtered herds’. (Albert Ehrenstein)

Poetic enthusiasm for military manliness can be found in Rainer Maria Rilke’s Fünf Gesänge (Five Songs) (1914), which conjure up a ‘War God’ and attribute to men an ‘iron heart’. Rilke’s form of heroism is, however a broken one, because it includes the ‘pain of battle’ and stresses the perspective of suffering and the victim: ‘May your own wandering flare up in the painful, the terrible heart.’ Austrian heroes, whom the literary texts present not so much as born but rather as temporary warriors, show themselves to be sensitive to pain and to have a inborn relationship with the natural world, while not losing completely their connection with the world of civilisation – a world which in many texts remains the home for which they yearn.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Cole, Laurence/Hämmerle, Christa/Scheutz, Martin (Hrsg.): Glanz – Gewalt – Gehorsam. Militär und Gesellschaft in der Habsburgermonarchie (1800 bis 1918), Essen 2011

Schmidt-Dengler, Wendelin: Ohne Nostalgie. Zur österreichischen Literatur der Zwischenkriegszeit, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2002

Wiltschnigg, Elfriede: Der „irrende Ritter“. Oskar Kokoschka, seine Beziehung zu Alma Mahler und der Erste Weltkrieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 373-391

-

Chapters

- Dreamers Who Turn into Heroes

- ‘Warriors on the Frozen Front’ – The War in the Alps as a Test of Manly Strengths

- The War as a ‘Technoromantic Adventure’

- Forms of Masculinity – Hierarchies, Rivals, Competitors

- Melancholy Men in Uniform – How Masculinity Becomes a Problem

- ‘Black Decay’ – Soldiers as Victims

- ‘The Flight Without End’? – The Warrior’s Homecoming

- ‘A New Race of Men’? – Ideologies of Masculinity in Post-War Austria