The Saturn censorship affair

-

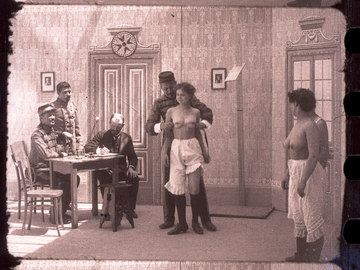

Bathing prohibited, film still, A 1907

Copyright: Filmarchiv Austria

Partner: Filmarchiv Austria

Special performances with erotic films were among the great attractions of the early cinema days. These ‘gentlemen’s evenings’, as they were called, included not only ‘spicy’ films but also films about surgical interventions, diseases and physical deformities.

One Austrian photographer also recognized the lucrative side of these productions, circulating nude photos alongside family pictures and portraits. In 1906 Johann Schwarzer began to produce erotic films, distributed by Saturn-Films. He was following the example of renowned French companies, which for some time had been successfully selling ‘lewd’ films. The subjects were also similar: bathing scenes, artists and models, or Oriental scenes. Schwarzer’s films were often more revealing than those of his competitors. Whereas the bodies of the bathing beauties in Pathé films were covered with fine fabrics, the young women in the Saturn productions were completely naked. There was nothing pornographic about Schwarzer’s pictures, however. The scenes simply showed a plausible situation for disrobing (visit to the doctor, bathing, nude drawings, etc.). Examples included Baden verboten (A 1907) or Weibliche Assentierung (A 1908–10).

The demand for ‘spicy’ films from Austria-Hungary was very great, and they were regularly advertised. Saturn distribution catalogue appeared on the market not only in German but also in Italian and French. The films were renowned throughout Europe as ‘Viennese subjects’. A complaint by the Austro-Hungarian consul in Tbilisi about the presentation of ‘obscenities from Vienna’ finally drew the attention of the authorities to the ‘Saturn affair’. According to the trade press, protests were also received by the diplomatic envoys in Berlin, Paris, London, Rome and Tokyo, leading to the confiscation of Saturn films and a court case. The Imperial and Royal District Court of Vienna banned the further distribution of the films, and the destruction of the film and printed material was ordered. The judgement entered into force on 15 February 1911, thus ending the activity of the first Austro-Hungarian film production company.

In Vienna ‘gentlemen’s evenings’ had already been forbidden in February 1910. Other crown lands also gradually introduced bans, making it impossible for erotic films to be distributed at all. During the First World War, ‘spicy films’ were once again in great demand, however, and they were shown to the troops in field cinemas.

Translation: Nick Somers

Achenbach, Michael: Die Geschichte der Firma Saturn und ihre Auswirkungen auf die österreichische Filmzensur, in: Achenbach, Michael/Caneppele, Paolo/Kieninger, Ernst: Projektionen der Sehnsucht. Saturn. Die erotischen Anfänge der österreichischen Kinematografie, Wien 1999, 75-102

Achenbach, Michael/Ballhausen, Thomas/Wostry, Nikolaus: Tresor 1, Saturn-Filme 1906–1910, Die erotischen Anfänge der österreichischen Kinematografie, Wien 2009

-

Chapters

- Film censorship – regulating what was shown

- The Saturn censorship affair

- Combatting ‘dirt and trash’

- Serving the public – the film and cinema industry before and during the First World War

- Organized propaganda: the film department of the War Press Office

- Focuses and aims of war film propaganda

- After the war – the National Film Headquarters: managing the past, warning about the present, and promoting new ideas