Focuses and aims of war film propaganda

The films made by the film department for the War Press Office had several functions: to support the war and the military activities and to put the treatment of prisoners of war, the ‘cultural status of the Monarchy’, the feeding of the population, the war industry, ‘the natural beauty of the Monarchy’ and the imperial household in the best possible light.

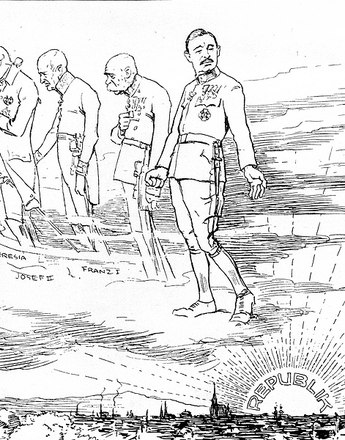

Visual reporting was designed not only as a topical means of propaganda both within the empire and in other countries, but also ‘to provide material for the future’ required by historians and the arts ‘to glorify the great achievements of war’. Thus, the idea of processing and showing the war after it had ended – in victory, of course – was already implanted.

Film propaganda was intended on the one hand to strengthen cohesion and belief in the Monarchy and the successful outcome of the war, both at home and among the troops. It was also designed to enhance the image of Austria-Hungary in neutral and allied foreign countries and in the occupied territories. It showed military, economic and cultural achievements with the aim of gaining long-term strategic and economic advantages. Austro-Hungarian productions were shown systematically for this purpose in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Romania, the Balkans, Turkey and initially also in the USA.

To safeguard film distribution and projection, the War Press Office called for targeted publicity, the exertion of pressure on distribution companies, and the direct promotion of the films with cinema companies. It had to be ensured that the films were not shown in public places in neutral countries so as to avoid the possibility of objections, discussion, loud protests or even acts of violence. The projections were to take place in closed rooms in which ‘the attention and interest remained concentrated on the images’. Military representatives were required to report regularly to the War Press Office on the success or failure of film propaganda.

Estimates differed on the effect of Austro-Hungarian films. Whereas people in the Netherlands complained about the ‘short and inferior films’ from Austria-Hungary, it was reported from Switzerland that the films were very popular and regarded as ‘the best of their type’. The reports were particularly euphoric from the Asian part of Turkey, where pictures of the Austro-Hungarian commanders and war films in particular were shown and attracted great interest. The war alliance between the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary and the German Reich no doubt helped to influence the positive public reaction. The newsreel reported accordingly on the War Demonstration by the Population at the Fatih Mosque (D 1914) in Constantinople.

Translation: Nick Somers

Mayer, Klaus: Die Organisation des Kriegspressequartiers beim k. u. k. AOK im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914–1918, Diss., Wien 1963

Schmölzer, Hildegund: Die Propaganda des Kriegspressequartiers im Ersten Weltkrieg 1914–1918, Diss., Wien 1965

-

Chapters

- Film censorship – regulating what was shown

- The Saturn censorship affair

- Combatting ‘dirt and trash’

- Serving the public – the film and cinema industry before and during the First World War

- Organized propaganda: the film department of the War Press Office

- Focuses and aims of war film propaganda

- After the war – the National Film Headquarters: managing the past, warning about the present, and promoting new ideas