Film censorship – regulating what was shown

Although cinematography was of increasing economic importance, for a long time there were no uniform regulations concerning the conditions and content of performances. For that reason, conflicts between authorities, morally concerned audiences and cinematograph operators were inevitable.

The new Gewerbegesetz [Trades Licensing Act] of 1907 made no mention of cinema, which remained covered by the Vagabunden- und Schaustellergesetz [Vagabond and Fairgrounds Act] of 1836. it was not until 1912 that a regulation was decreed specially for cinematographic businesses, which finally treated the cinema as an autonomous form of entertainment.

Approval of content was based on the 1850 Theatergesetz [Theatres Act] or an 1852 decree forbidding immoral performances. The authorities interfered above all in response to complaints by indignant citizens protesting against indecent and wanton performances. From 1898 films were monitored locally by a policeman who was present at the projection.

The increase in cinematographic offerings called for a more permanent regulation. In 1907 the first regional censorship was introduced in Vienna, which allowed the police to forbid performances in advance. Film material could even be destroyed following a complaint. In 1909 accompanying texts and publicity material were also monitored by the police. A regulation by the Ministry of the Interior in coordination with the Ministry of Public Works recommended in 1912 that the censorship decisions of the Viennese authorities should be followed, but there were other regional censorship offices in the Monarchy ¬– in Linz, Innsbruck, Graz, Salzburg, Klagenfurt, Trieste, Zadar, Prague, Brno, Lemberg (Lviv), Ljubljana, Opava und Czernowitz (Chernivtsi).

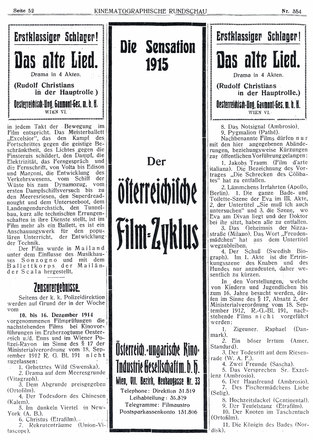

Political censorship was stepped up with the start of the First World War. Films with military and political content were now often forbidden. In December 1914 an official memorandum forbade the presentation of films from ‘enemy states’. Already imported films from the ‘enemy territory’ could be performed provided that the company insignia and indications of the country of origin were removed. In 1915 a censorship office was established in the Austro-Hungarian War Archive, which verified the content and political message of all military films.

Political censorship was lifted on 30 October 1918 by decision of the provisional National Assembly. Film censorship remained in force. Standardization remained an issue in the First Republic, and no solution was found at this time, as the provinces were unwilling to abandon their authority in this regard.

Translation: Nick Somers

Ballhausen, Thomas: Geschnitten, Verboten, Vernichtet. Notizen zur österreichischen Filmzensurgeschichte bis 1938, in: Biblos 51 (2002), 203-214

Ballhausen, Thomas/Caneppele, Paolo (Hrsg.): Die Filmzensur in der österreichischen Presse bis 1938, Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- Film censorship – regulating what was shown

- The Saturn censorship affair

- Combatting ‘dirt and trash’

- Serving the public – the film and cinema industry before and during the First World War

- Organized propaganda: the film department of the War Press Office

- Focuses and aims of war film propaganda

- After the war – the National Film Headquarters: managing the past, warning about the present, and promoting new ideas