In memoriam Dr. Schober, film still, A 1932

Copyright: Filmarchiv Austria

Partner: Filmarchiv Austria

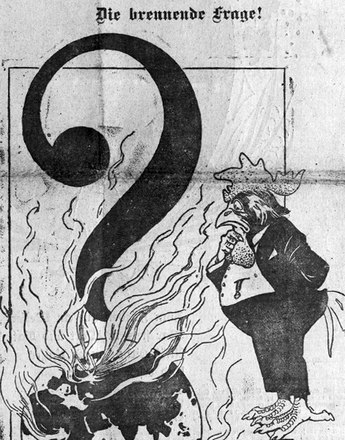

The shadow side of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the First World War has barely impinged on the visual memory as there is an absence of film material. Poverty, disease, social arrogance, exclusion, national and ideological conflicts and finally the atrocity of war and mass killing are hinted at in but a few films.

It was not until the First Republic had been proclaimed that the Staatliche Filmhauptstelle drew attention to grievances and sought to provide information. The aspects that had been covered over during the Monarchy were now being captured on camera.

In 1918 the Habsburg empire was materially depleted. The situation became worse after it had been dissolved as a traditional economic area. The exchange of raw materials and food between the former crown lands of the Danube Monarchy came to a standstill at times. In 1918/19 there were no supplies left to exchange. Urban authorities and representatives of the victorious powers noted that through the blockade of food supplies from Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary, the population was receiving only 750 instead of the required 2,000 calories per day. Endless queues of needy people would form whenever anything was being distributed. The cessation of Czechoslovakian coal deliveries affected not only industry and transport companies but also private households.

One film giving insight into the distress in post-war society was produced from archive material on the death of the former Vienna police president and federal chancellor Johann Schober in 1932 (In Memoriam Dr. Schober, A 1932): food rations and self-help by collecting wood for burning in nearby forests provided only temporary aid. Unchallenged by the authorities, the population took things into their own hands. Entire forests were cut down to obtain the necessary fuel.

Cold, hunger and disease struck mercilessly, particularly in Vienna. Medical examinations produced alarming results: 80 per cent of all children in Vienna were considered severely undernourished. There was also an unusually high incidence of tuberculosis compared with other countries. The city council responded to the health consequences of the poor living conditions with modern methods, and a significant drop in mortality was achieved even in the 1920s; and yet according to examinations in primary schools, almost 50 per cent of Viennese children in early 1927 were tuberculous. The production Das Kinderelend in Wien (A 1919) shows the real state of post-war society, particularly as it affected children. Then and now images show how the general health of the population has declined. Food is foraged for in rubbish heaps, and families live in railway wagons because of the shortage of housing. Rickets, scrofula and tuberculosis are rampant. There are also war invalids among the children – belated victims of the war.

Translation: Nick Somers

Eigner, Peter/Helige, Andrea (Hrsg.): Österreichische Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Wien/München 1999

Sandgruber, Roman: Ökonomie und Politik. Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, Wien 1995

-

Chapters

- Imperial and Royal myth in film

- Presentation of the imperial household: pictorial icons

- What the films didn’t show 1: Social contrasts

- What the films didn’t show 2: Religious diversity

- What the films didn’t show 3: nationalist conflicts

- Lack of resources and wartime financial difficulties on film

- Film documents: after the disaster