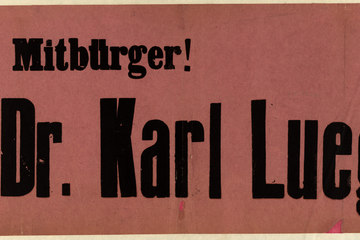

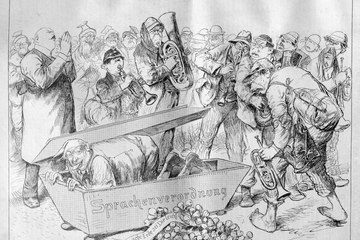

Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

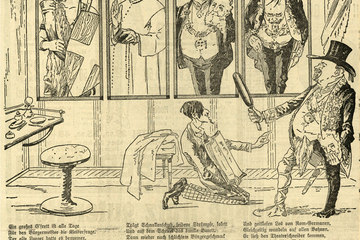

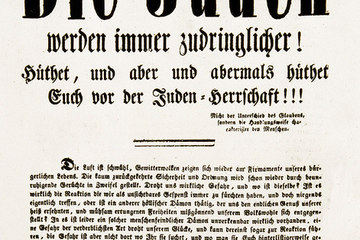

The beginnings of the Christian Social Party are to be found firstly in the Catholic Social Reform movement of a certain Freiherr Karl von Vogelsang, and secondly, in the Vienna small trades movement, whose aim was to maintain the competitiveness of small businesses against large-scale industry.