In the elections to the Imperial Diet of 1891, the Christian Socials emerged ahead of conservative-clerical groupings, making its first appearance as an autonomous political movement.

The Christian Socials entered the Imperial Diet with 13 members (3.7%) and founded its own parliamentary party, the Free Association for Economic Reform on a Christian Basis. Although Karl Lueger was already using the term Christian Social Party as early as 1891, it had until this date been a loose group of heterogeneous forces that still needed to be welded into a unitary party.

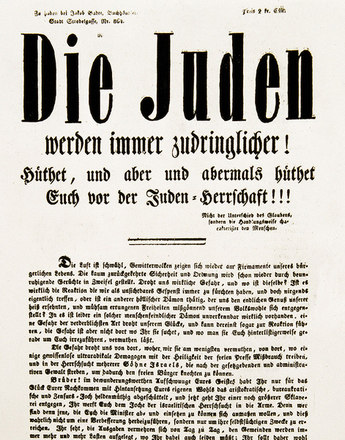

Anti-Semitism played an important role in the creation of the Christian Social movement, and was a major factor for the integration and mobilisation of the party's own Catholic clientele. The middle class and the petty bourgeoisie, the artisans and small businesses were particularly susceptible to Lueger's anti-Semitism. The blame for the financial difficulties that threatened the middle classes as a result of overpowering competition from industry was laid at the door of capitalism and Jewish liberalism.

The Christian Social movement finally succeeded in extending its influence from the middle-class and petty bourgeoisie to the lower clergy and the Catholic rural population. On 21 September 1892, Leopold Kunschak founded the Lower Austrian Christian Social Workers Association, the aim of which was to protect the interests of Christian workers. In addition, more and more of the property-owning classes joined the Christian Social Party in the 1890s and later.

Its anti-Semitism gave rise to serious concerns amongst the conservatives and the higher clergy. In the 1890s, the episcopate complained twice to the Pope about the party, accusing it of anti-Semitism, incitement of the population and disobedience towards the authority of the bishops. The dispute ended with a victory for the party, with Pope Leo XIII approving its programme in his social encyclical "Rerum novarum" and giving Karl Lueger his blessing.

There was also distrust of the Christian Socials at Court, and for this reason the Emperor initially refused to confirm Lueger in his office following his election as Mayor of Vienna. The United Christians were highly successful in the Vienna City Council elections of 1895, bringing the liberal dominance in the Vienna City Hall to an end. Lueger was elected Mayor, but was only confirmed in his office by the Emperor two years later.

Despite these successes, the Christian Social influence was restricted to Vienna and neighbouring Lower Austria. In the 1897 Imperial Diet elections, the Christian Socials saw their position confirmed in this region, while also making advances in the provincial towns and the Alpine regions.

As party leader and an outstanding demagogue, Lueger played a decisive role in the success of the Christian Social movement and its rise to become a mass party. Jacques Hannak, an opponent of Christian Social ideology put this very accurately: "The success of the Christian Social movement was not due to the moral sayings and pious wishes in the social doctrines of a Vogelsang, nor to the sticking plaster of the clerical conservative beggar's soup and social policies of a Prince Aloys Liechtenstein, nor to the noisy roughness of an Ernst Schneider, nor to the papal encyclicals of a Leo XIII, but rather to the demagogical talent of one man" – Karl Lueger.

Translation: David Wright

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Hanisch, Ernst: Österreichische Geschichte 1890-1990. Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 1994

Hanisch, Ernst/Urbanitsch, Peter: Grundlagen und Anfänge des Vereinswesens, der Parteien und Verbände in der Habsburgermonarchie, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VIII. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft. 1. Teilband. Vereine, Parteien und Interessenverbände als Träger der politischen Partizipation, Wien 2006, 15-111

Kriechbaumer, Robert: Die großen Erzählungen der Politik. Politische Kultur und Parteien in Österreich von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1945, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2001

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Urbanitsch, Peter: Politisierung der Massen, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 106-118

Vocelka, Karl: Geschichte Österreichs. Kultur – Gesellschaft – Politik, 3. Auflage, Graz/Wien/Köln 2002

Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 289-486

Quotes:

"The success of the Christian Social movement …“: Hannak, Jacques: Im Sturm eines Jahrhunderts. Eine volkstümliche Geschichte der Sozialistischen Partei Österreichs, Wien 1952, 86, in: Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997, 493 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'