The 1890s saw an increasing surge of the nationalities struggle and hence also of German nationalism. The national camp was boosted by the school dispute in Celje in 1895 and the language regulation for Bohemia and Moravia issued by Minister Presisdent Badeni in 1897.

On 7 June 1896, the German People's Party was founded under Otto Steinwender. It pursued a policy of supporting the state and was always ready to make concessions to the Crown. In this way, it promoted the interests of the German Reich more effectively than the radicalism of Schönerer's supporters achieved.

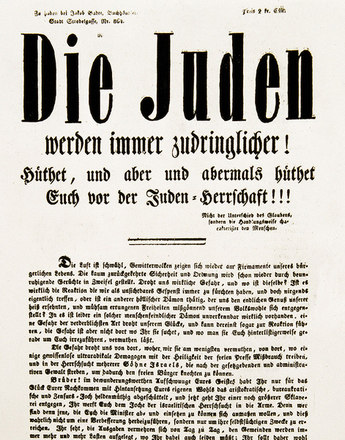

Thanks to the 1896 electoral reform and the extension of suffrage to all male citizens over 24, the German Nationals were able to make considerable gains in the Imperial Diet elections of 1897. Georg von Schönerer also returned to Parliament. The German Nationals profited from the lack of a concept of an Austrian state and empire. With skilful propaganda, they succeeded in arousing sympathy for the German Reich, Bismarck and the Hohenzollerns, and in fomenting hatred of the Jews and the Slav peoples. They recruited their most determined supporters from the German gymnastics and sport associations, the choral societies, the student fraternities and the national school and rifleman associations. Their anti-Semitism and their "teutomania" was popular above all amongst the urban petty bourgeoisie and the inhabitants of the language border regions who felt threatened by their Slav neighbours.

The differences between Schönerer's Pan-Germans and the other German National groups intensified. Schönerer's supporters pursued an anti-Austrian policy, and their radical anti-Catholic agitation, expressed in the "Away-from-Rome Movement", was not supported by the other parties in the national camp. Schönerer's party ultimately split, leading to the foundation of the Free Pan-Germans, who later adopted the name German Radicals. Karl Hermann Wolf, the man at the party helm, was a skilled agitator like Schönerer but pursued a realistic and loyal policy.

A further split within the national camp resulted with the foundation of the German Workers Party in 1904 and the German Agricultural Party in 1905.

The first Imperial Diet elections of 1907 to be conducted on the basis of general, equal, direct and secret male suffrage weakened the German Nationals.

Following the defeat, voices were raised in favour of a German liberal federation, which was finally founded in 1910 under the name German National Federation. This was a union of the German People's Party, the German Progress Party, the German Agricultural Party and the German Radicals. They all pursued a national policy on an Austrian basis and supported the preservation of the monarchy. A large part of the votes lost were regained in the Imperial Diet elections of 1911, with the German National Federation emerging as the strongest parliamentary group with 104 deputies (20.2%) – in contrast to the Christian Socials with only 74 (14.3%) and the Social Democrats with 44 (8.5%) seats.

At the beginning of the war, the German National Federation generally supported the government's actions and its decision in favour of war. The German Nationals now demanded the confirmation of the alliance with the German Reich in the Constitution, and the creation of a common customs territory. Continuing the lines of the traditional German National objectives, Austria was still to be protected against the Slavs achieving a majority, and the German language was to be the only official and administrative language. As the Habsburg Monarchy gradually fell apart as a result of the nationalities problem, National circles hoped for the union of the German-speaking areas with the German Reich.

Translation: David Wright

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005

Fuchs, Albert: Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918, Wien 1984

Kriechbaumer, Robert: Die großen Erzählungen der Politik. Politische Kultur und Parteien in Österreich von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1945, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2001

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Urbanitsch, Peter: Die Nationalisierung der Massen, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 119-125

Wandruszka, Adam: Die Habsburgermonarchie von der Gründerzeit bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 4-19

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'