The defeat of Austria by the Prussians at the Battle of Königgrätz in 1866 and the subsequent withdrawal of the Habsburg Monarchy from the German Federation led to a major regrouping within the German National camp.

While the one group rejected the Habsburg state and espoused the cause of the unification of all Germans within a German nation state, the others accommodated themselves with the monarchy and focussed their policies on protecting German traditions against the increasing Slav influence.

Until well into the 1870s, the German National movement lacked political clout. At parliamentary level, it was initially only able to develop its ideas within the liberal Constitutional Party. In 1871, this split into the Liberal Club and the Progressive Club with its German national orientation, whose members included the later German National leader, Georg Ritter von Schönerer. Although the latter's demagogic skills enabled him to spread the German national idea, his radical political style prevented him from acquiring any great significance. Nevertheless, Schönerer's ideological group became a gathering of all the national tendencies that were also to be seen in modified or weakened form in the other national groups.

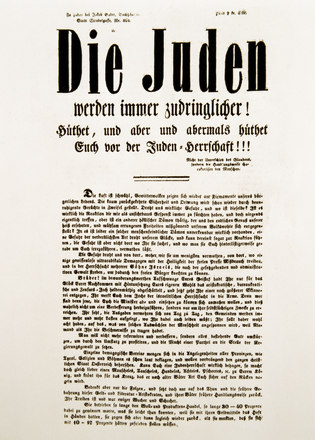

Schönerer, a champion of the Smaller German idea, argued vehemently against the Habsburg state and pleaded in favour of the unification of the German-speaking territories of Austria with the German Reich. He pursued a radical German national course, inveighing against capitalists, Jews and the Catholic Church, with his "Away-from-Rome Movement" recommending conversion from Catholicism to the more German-friendly Protestantism. Aurelius Polzer, one of Schönerer's supporters, described the national ideology as follows: "German and loyal, outright and true, / Free of Jews, free of Czechs, / Free of priests and free of foreigners, / In short, straight and pure."

Schönerer succeeded in combining the reactionary solutions he advanced with democratic or even progressive ideas. He left the Liberal Party at the end of the 1870s, creating his own two-man party together with Heinrich Fürnkranz, the mayor of Langenlois in Lower Austria. In 1882, the German National Association was founded, whose members included not only Schönerer but also the later Social Democrats Engelbert Pernerstorfer und Victor Adler, the later Christian Social Robert Pattai, the historian and journalist Heinrich Friedjung and the German National politician Otto Steinwender.

The 1882 Linz Programme set out the most important principles of the German National Association. It included national demands, such as the wish for closer links with the German Reich and for the creation of a common customs territory. At the same time, it contained a number of social and democratic demands: the broadening of the suffrage, the freedom of association and the press, a progressive income tax, regulated working hours and the reduction of child and women's labour. Since Jewish members were involved in the creation of the Linz Programme, it did not contain any Jewish clauses despite Schönerer's open espousal of anti-Semitism. It was only in 1885, when the list was increased by the addition of a demand for the "elimination of the Jewish influence on all fields of public life" that Adler, Friedjung and Pernerstorfer left the Association. Since in the House of Deputies the programme was only supported by Schönerer and Fürnkranz, it had no direct consequences at parliamentary level. However, it became the most important programmatic manifesto of the German National movement.

Translation: David Wright

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Kaisertum und Doppelmonarchie, Wien 2003

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Fuchs, Albert: Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918, Wien 1984

Kriechbaumer, Robert: Die großen Erzählungen der Politik. Politische Kultur und Parteien in Österreich von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1945, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2001

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 289-486

Quotes:

"German and loyal ...“: Aurelius Polzer, quoted from: Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997, 489 (Translation)

"elimination of the Jewish …“: Fuchs, Albert: Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918, Wien 1984, 182 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'