From the middle of the 1860s, the liberals made huge gains and levered liberalism into power. However, the liberal age proved to be short-lived, coming to an abrupt end with the electoral defeat of the Constitutional Party in 1879.

In 1867, the Reichsrat adopted a constitution with a list of basic rights, the right of association and assembly was published and in 1869 the liberal Imperial Primary School Act reduced the influence of the Church in the field of education. In 1870, finally, the Concordat concluded between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Catholic Church in 1855 was set aside, and the 1873 electoral reform introduced direct elections to the Reichsrat.

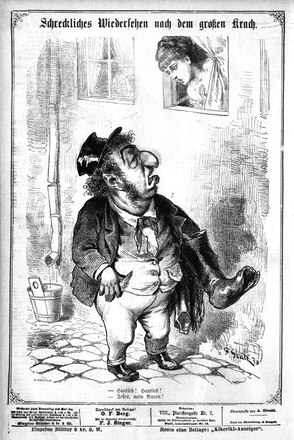

From 1867 to 1879, the German Liberals held the majority of seats in the Reichsrat, where they sat as the "Constitutional Party". The focus of their economic policies was on the foundation of companies, banks and joint stock corporations and the encouragement of the population to participate in these – often speculative – ventures. However, following the stock exchange crash in 1873 trust in liberal economic policies vanished, as did the power of the Constitutional Party, already considerably weakened by internal policy disagreements. A section of the German Liberals now turned more to German nationalism. Essentially, this was a conflict between the older and younger generations that ultimately led to a split in the liberals and the foundation of the Liberal German Progressive Club.

Within the liberal camp, different political directions developed that were adapted by the later large parties – the Social Democrats, the Christian Socials and the German Nationals. Although the liberal heritage lived on in them, their common origin lay in their opposition to the governing liberalism and in their attempts to combat the social evils within the multinational state. In the 1882 Linz Programme, the representatives of the left wing of the collapsing liberal movement, including the later party leaders Georg Ritter von Schönerer (German Nationals), Robert Pattai (Christian Socials) and Victor Adler und Engelbert Pernerstorfer (Social Democrats), agreed on the need to deal with the social and national problems. Alongside the concerns of the German Nationals – German should be the language of the state – the demands related to the fiscal system, representation of worker interests, nationalisation of the railways, extension of suffrage and freedom of press, association and assembly.

Liberalism had no answer to the national and social problems that were becoming more and more apparent under the liberal government – the miserable living conditions of the growing urban proletariat, the economic difficulties of the lower middle classes, the craftsmen and tradesmen, and the intensifying conflict between the various nationalities. Liberalism only insufficiently represented the interests of the lower middle classes and the workers, and voted against an extension of the franchise in order to secure the political hegemony of the propertied middle class. In contrast to the liberals, the new political movements of the Social Democrats, the Christian Socials and the German Nationals, however, addressed the urgent social questions of the Habsburg Empire and the interests of the part of the population previously excluded from political decision-making processes. Notwithstanding their common origins and collaboration, the later party leaders of the three major camps were finally persuaded by their different ideological orientations to go their separate ways.

Translation: David Wright

Buchmann, Bertrand Michael: Kaisertum und Doppelmonarchie, Wien 2003

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Fuchs, Albert: Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918, Wien 1996

Hanisch, Ernst/Urbanitsch, Peter: Grundlagen und Anfänge des Vereinswesens, der Parteien und Verbände in der Habsburgermonarchie, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VIII. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft. 1. Teilband. Vereine, Parteien und Interessenverbände als Träger der politischen Partizipation, Wien 2006, 15-111

Kann, Robert A.: Geschichte des Habsburgerreiches 1526-1918, 3. Auflage, Wien/Köln/Weimar 1993

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Vocelka, Karl: Karikaturen und Karikaturen zum Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs, Wien/München 1986

Vocelka, Karl: Geschichte Österreichs. Kultur – Gesellschaft – Politik, 3. Auflage, Graz/Wien/Köln 2002

Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 289-486

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'