In the course of the 1848 Revolution, the liberal opposition with its critical attitude to the government and led above all by the intelligentsia, the students and the propertied and educated middle-classes, who were weary of being excluded from political participation, demanded the drafting of a constitution. This constitution was to guarantee the formation of a Parliament and the right to the freedom of opinion and freedom of assembly.

The revolutionary forces objected to the corporate society and its privileges, and to Metternich's restrictive system in which infringement of human rights, spying and censorship were the order of the day.

As early as 1847, the Austrian playwright Johann Nestroy gave expression to criticism of Metternich by singing the following lines at the opening of the Carltheater in December 1847:

"In the school, I give thanks / My hands on the bench / Listing to the lecture / Without falling asleep / The book is open / I daren't chatter /Like an iron monkey / Because otherwise I'll be punished / This terrible pressure / Keeps us from growing."

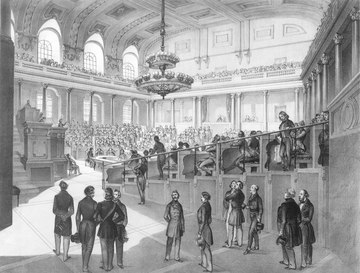

On 13 March 1848, revolution broke out during an assembly of the Lower Austrian Estates in the Landhaus in Herrengasse and a demonstration of citizens and students taking place at the same time in the Vienna inner city. The simultaneous insurrection of the urban proletariat in the Viennese suburbs played a major role in the initial successes. On the same day Prince Metternich resigned and fled to England. A constitution was adopted on 29 April, and on 22 July 1848 Archduke Johann opened the Reichstag, the parliament of the Habsburg Monarchy. Within this institution, political parties formed for the first time – the Centre Party, an assembly of Conservatives loyal to the government (large estate owners, the aristocracy, civil servants and some of the peasantry), the Leftist Club (liberals) and the representatives of the various nationalities.

However, the dissolution of the Reichstag in March 1849 and the revocation of the constitution by the New Year's Eve Patent of 1851 put a sudden end to the political participation that had been achieved. It was not until the February Patent of 1861, which provided for the formation of a Reichsrat, that at least the propertied and educated classes (the aristocratic large landowners, industrialists, the urban middle classes and wealthy peasants) were able to participate in the political decision-making process. Political parties formed once again within the Reichsrat, but had no structured organisation, being instead a loose grouping of politically like-minded individuals. The proposal was for a two-chamber system with a House of Lords consisting of appointed members and a House of Representatives whose members were not, however, elected directly but instead were delegated by the provincial diets. Amongst the members of the provincial diets, a distinction must be made between elected members and virilists. University rectors, Catholic and Orthodox bishops were granted what were known as virile votes and were automatically members of the provincial diet in whose region the university or diocese in question was located. Elections to the provincial diets were held in four classes of electors ("curiae"). These were the curiae representing the large landowners, the chambers of trade and commerce, the towns and markets and a curia representing the rural communities. However, the curial electoral system meant that the votes were differently weighted. In the curia for the rural communities, each representative was elected by 8,100 voters, while in the towns one seat corresponded to an average electorate of 1600. On the other hand, one member of the diet represented an average of 24 voters in the chambers of commerce, and 51 in the curia of the large land-owners. In addition, the franchise was only held by those groups of the population that paid a certain amount of tax, thereby continuing to exclude broad sectors of the population from political participation. One exception was the intelligentsia – clergymen, civil servants, officers, university graduates, teachers and honorary citizens – whose level of education or professional position gave them the right to vote irrespective of the tax they paid.

Translation: David Wright

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Hanisch, Ernst: Österreichische Geschichte 1890-1990. Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 1994

Hanisch, Ernst/Urbanitsch, Peter: Grundlagen und Anfänge des Vereinswesens, der Parteien und Verbände in der Habsburgermonarchie, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VIII. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft. 1. Teilband. Vereine, Parteien und Interessenverbände als Träger der politischen Partizipation, Wien 2006, 15-111

Kořalka, Jiří: Die Anfänge der politischen Bewegungen und Parteien in der Revolution 1848/1849, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VIII. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft. 1. Teilband. Vereine, Parteien und Interessenverbände als Träger der politischen Partizipation, Wien 2006, 113-143

Melik, Vasilij: Zusammensetzung und Wahlrecht der cisleithanischen Landtage, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VII. Verfassung und Parlamentarismus. 2. Teilband. Die regionalen Repräsentativkörperschaften, Wien 2000, 1311-1352

Nick, Rainer/Pelinka, Anton: Parlamentarismus in Österreich, Wien/München 1984

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Urbanitsch, Peter: Die Nationalisierung der Massen, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 119-125

Vocelka, Karl: Geschichte Österreichs. Kultur – Gesellschaft – Politik, 3. Auflage, Graz/Wien/Köln 2002

Quotes:

"In the school, I give thanks …“: Nestroy, Johann: Die schlimmen Buben in der Schule. Werke Nr. 5, 14, quoted from: Hanisch, Ernst: Österreichische Geschichte 1890-1990. Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 1994, 268 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'