Although the German National movement made only very slow progress in the 1870s, its significance increased in the following years, driven by the Alliance (Dual Alliance) concluded between the Habsburg Monarchy and the German Reich in 1879 and the pro-Slav policies of the Minister President Graf Eduard Taaffe.

The German Nationals made considerable gains in the Imperial Diet elections of 1885, but all attempts to unify the deputies who had been elected on the basis of German liberal or German national principles failed. The liberal Constitutional Party finally split into a German-Austrian Club of old liberals supporting the composite state idea of the Habsburg Monarchy, and a German Club around Otto Steinwender.

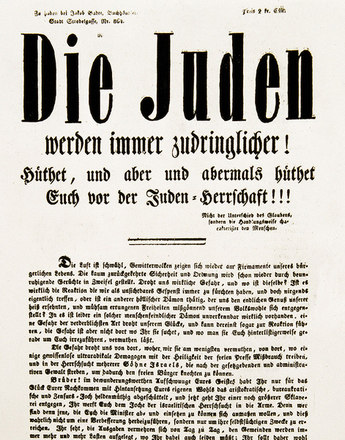

Since Schönerer's anti-Semitic attitude excluded him from the German Club, he founded the Federation of German Nationals in the same year. As early as 1887 differences of opinion concerning the Jewish question and economic matters led to split in the German Club and the foundation of the German National Union. With the participation of Otto Steinwender, this became the German National Party in 1891 and the German People's Party in 1896.

Schönerer and Steinwender's political positions – Steinwender's active participation in the state and Schönerer's rejection of the Habsburg Monarchy – dominated the further development of the national camp. Schönerer's policies, his anti-Semitism and his aversion towards Austria became increasingly radical. Despite the Alliance concluded between the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the German Reich in 1879 – the Dual Alliance – he refused to participate in affairs of state. Steinwender's supporters, on the other hand, pursued a policy of loyalty to the state and supported the Austrian government's implementation of the Alliance. Schönerer's supporters, who were always only a small minority, were vocal in their support for a strengthening of the Alliance but prevented its implementation through their policies.

The German Nationals were often accused of "Prussian pestilence" and of "peering" beyond the Habsburg borders. The German-speaking Bohemian writer Josef Willomitzer replied in a poem: "We do not peer, we look over frankly and freely, we look freely and openly, we look steadfastly, we look cheerfully into the German Fatherland."

In 1888, Schönerer briefly left political life. Having led an attack on the editorial offices of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt for announcing the death of the German Emperor Wilhelm I a few hours before his actual death, Schönerer was sentenced to prison, stripped of his aristocratic title and required to resign from the Imperial Diet.

The structure of the national camp remained unchanged after the Imperial Diet elections of 1891. Ernst Plener's liberals, who had adopted the name United German Left in 1888, formed the strongest party with over 100 deputies (28%). The German National sector was represented by the German National Party, the successor to the German National Union under Otto Steinwender, and Schönerer's Pan-Germans.

Translation: David Wright

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Fuchs, Albert: Geistige Strömungen in Österreich 1867-1918, Wien 1984

Kriechbaumer, Robert: Die großen Erzählungen der Politik. Politische Kultur und Parteien in Österreich von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1945, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2001

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Vocelka, Karl: Karikaturen und Karikaturen zum Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs, Wien 1986

Vocelka, Karl: Geschichte Österreichs. Kultur – Gesellschaft – Politik, 3. Auflage, Graz/Wien/Köln 2002

Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 289-486

Quotes:

"We do not peer …“: Josef Willomitzer, quoted from: Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 380 (Translation)

"Prussian pestilence": Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 379 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'