After the outbreak of war most Social Democrats – at least in the first two years of the war – pursued a “truce policy”. Very little was left of their pre-war pacifist commitment; they now supported the war.

Before the war the Social Democratic party had asserted that lasting peace could be achieved only by abolishing the capitalist social order, which was seen to be reinforced by the militarist structure. After 1914, by contrast, they were afflicted with “major paralysis”, as the historian Christoph Gütermann puts it. This attitude ended only in 1916–17 after Friedrich Adler had assassinated prime minister Stürgkh in October 1916, and Karl Renner’s patriotic Socialist line ran aground at the 1917 party congress.

Before 1914, in particular the Social Democratic women’s movement, which had links with the international socialist peace movement, came out vehemently against militarism and war. According to historian Susan Zimmermann, paragraph 30 of the statutes prevented it from being incorporated in the party as a whole, and as a result its representatives were able “to adopt more radical positions”. At the same time, however, this weakened their influence on the party as a whole and its political line. Leading members of the working women’s movement like Adelheid Popp were frequently heckled or censored by controlling party bodies when speaking against war and militarism. Anti-military ideas and appeals for peace were heard mainly at the large voting right demonstrations. At one such demonstration in Vienna, Adelheid Popp stated, for example: “We protest against millions being wasted for killing and fratricidal war. We want the killing machinery to be dismantled and these millions to be used for the needs of the people!”

Austrian Social Democratic women also took part in an international peace demonstration in Berlin in April 1914 and spoke against militarism and in favour of worldwide peace. A few months later, however, with the outbreak of war this commitment ceased and the majority of Social Democratic women adopted the pro-war line of the party as a whole, reflected amongst other things in their participation in the Women’s War Aid Action. From 1915, however, there were appeals at practically all meetings of the women’s worker movement for a rapid end to the war.

Translation: Nick Somers

Anderson, Harriet: Utopian Feminism. Women’s Movements in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna, New Haven 1992, 125

Flich, Renate: Frauen und Frieden. Analytische und empirische Studie über die Zusammenhänge der österreichischen Frauenbewegung und der Friedensbewegung mit besonderer Rücksicht des Zeitraumes seit 1960, in: Rauchensteiner, Manfried (Hrsg.): Überlegungen zum Frieden, Wien 1987, 410-461

Gütermann, Christoph: Die Geschichte der österreichischen Friedensbewegung 1891-1985, in: Rauchensteiner, Manfried (Hrsg.): Überlegungen zum Frieden, Wien 1987, 13-132

Lackner, Daniela: Die Frauenfriedensbewegung in Österreich zwischen 1899 und 1915, Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien, Wien 2008

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: Die österreichische Frauenbewegung und der Krieg, in: Alfred Pfoser/Andreas Weigel (Hrsg.), Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 82-87

Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.), Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 88-96

Quotes:

„major paralysis“: quoted from: Gütermann, Christoph: Die Geschichte der österreichischen Friedensbewegung 1891-1985, in: Rauchensteiner, Manfried (Hrsg.): Überlegungen zum Frieden, Wien 1987, 73

„This attitude ended only …“: Gütermann, Christoph: Die Geschichte der österreichischen Friedensbewegung 1891-1985, in: Rauchensteiner, Manfried (Hrsg.): Überlegungen zum Frieden, Wien 1987, 73

„to adopt more radical positions“: quoted from: Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.), Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 90

„[…] this weakened their influence …“: Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.): Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 90

„We protest against millions ...“: Adelheid Popp, quoted from: Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.), Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 90

„[...] international peace demonstration in Berlin …“: Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.), Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 90

„From 1915, however, there were appeals …“: Zimmermann, Susan: Die österreichische Frauen-Friedensbewegung vor und im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Forum Alternativ (Hrsg.): Widerstand gegen Krieg und Militarismus in Österreich und Anderswo, Wien 1982, 93

-

Chapters

- “Lay down your arms” – Bertha von Suttner, the most prominent Austrian peace activist

- ‘The Austrian Society of Friends of Peace’– a brief episode?

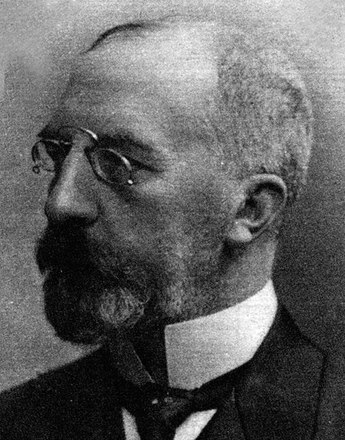

- Alfred H. Fried and the peace movement during the war – censorship and derision

- ‘The League of Austrian Women’s Associations’ and the end of peace activities

- The Hague or the “betrayal” of the warring nation

- ‘… and tomorrow we will start cheerily canvassing for peace.’

- Peace and social issues

- The idea of the ‘peace-loving woman’?

- Peace and the Church – Thou shalt not kill!

- Peace and language – peace and the Esperanto movement

- Para Pacem – an Austrian peace movement with a difference

- Individual peace initiatives – Julius Meinl and Heinrich Lammasch

- ‘… surely this war must end some time?!’