When concrete steps for a coup d’état were being taken in Prague in autumn 1918, the protagonists were surprised at the passivity shown by the organs of government, exposing the inner exhaustion of the old system and the lack of orientation in the Viennese central government. The sole objective seemed to be the avoidance of a violent escalation.

In August 1918 the situation for the Imperial-Royal Army had deteriorated so severely that rumours arose of a prompt military collapse. The civilian administration had foundered on the provisions crisis and had lost its authority in the eyes of the people; now, with the army, the last pillar supporting imperial power was beginning to totter. Those proposing state independence for the Czechs and Slovaks in Prague saw this as a window of opportunity for the crucial step. Preparations were made for a transfer of power.

The separatist circles in the Czech political scene found their most influential platform in the Czechoslovakian National Committee surrounding Karel Kramář; they used its network to liaise with officers of the Imperial-Royal Army who were gauged as loyal to the Czechoslovakian cause. Persons of trust were also found among civil servants and government officials: customs officers were to close the borders in the case of emergency and railway employees to paralyse transportation and so obstruct troop movements. A key role was played through the ideas of the national Czech gymnastic association Sokol, which ran a dense network of branches and could thus connect up with the masses.

When in September 1918 the Western Powers acknowledged the interim government-in-exile of Czechoslovakia in Paris, its spokesman Edvard Beneš urged the politicians at home not to enter into any negotiations whatsoever with the Imperial Government. This was maintained by all parties. On 11 October a delegation of Czech politicians was invited to an audience with Emperor Karl, an occasion which would have offered them participation in the government – but they rejected all cooperation with the Viennese central authorities.

On the contrary – the members of the National Committee demanded that diplomatic passports be issued to them so as to be able to meet up with representatives in political exile in neutral Switzerland. And when the passports – astonishingly – were issued by the Austrian authorities, this seemed in Prague as good as being given carte blanche: contacting Masaryk was no longer judged to be high treason.

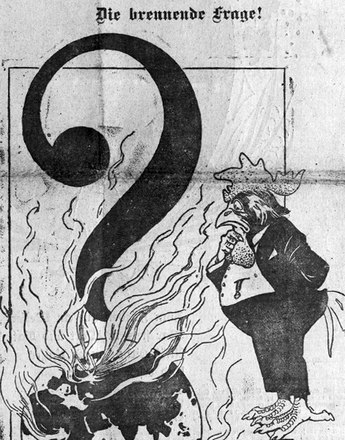

And now the left-revolutionary camp was beginning to rev up its activities. The Social Democrats called for a general strike on 14 October and tried to assume leadership. However, the planned declaration of a Socialist Czechoslovakian Republic foundered. For the national circles of the bourgeoisie this was a warning that time was running out. The fear spread of a Bolshevist revolution.

Karl I’s Peoples’ Manifesto published on 16 October was rejected by the National Committee, which already saw itself as sole voice of the “Czechoslovakian Nation”. The reason it gave for its rejection was that the imperial offer of a restructuring of the Monarchy according to ethnic principles only affected the Austrian half of the empire. This would have thwarted the demand for unification with the Slovaks counted as belonging to the Hungarian half of the empire. Apart from which, a federalisation of the Monarchy would have split the Bohemian regions into a German and a Czech part, which was also rejected by the Czechs because of the demand for retaining the historical borders.

This half-hearted and belated offer of Karl’s also exposed the emperor’s loss of authority; he had lost his effective power. On 26 October the Czech media published an appeal for peace and order by Edvard Beneš, the general secretary of the interim government-in-exile of the still virtual state of Czechoslovakia. The fact that a declaration by Beneš was passed by the censorship – a man who previously had been wanted for high treason – was a clear signal to the masses that the authorities wished to avoid an escalation – regardless of who achieved this.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Gottsmann, Andreas (Hrsg.): Karl I. (IV.), der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Donaumonarchie, Wien 2007

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Kučera, Rudolf: Muži října 1918. Osudy aktérů vzniku Republiky Československé [Die Männer des Oktobers 1918. Schicksale der Akteure der Entstehung der Tschechoslowakischen Republik], Praha 2011

Pacner, Karel: Osudové okamžiky Československa [Schicksalhafte Momente der Tschechoslowakei] (3. Aufl.), Praha 2012

Šedivý, Ivan: Češi, České země a velká válka 1914–1918 [Die Tschechen, die Böhmischen Länder und der Große Krieg 1914–1918], Praha 2001

-

Chapters

- Delenda Austria – Austria must be destroyed!

- The aim of state independence: from Utopia to a programme for the masses

- Preparing for the Coup

- The Day of the Coup: 28 October 1918

- The Founding of Czechoslovakia

- The Czechoslovakian Republic as Successor State to Austria-Hungary

- The Czechoslovakian Legions

- The Fall of the Symbols of Habsburg Rule